By the fin-de-siècle, Ittenbach was widely regarded as one of the century’s foremost painters of modern devotional art.

Provenance

Private collection, Germany

Sale, Van Ham, Cologne, 20 November 2009, lot 327

Private collection, California (acquired at the above sale)Catalogue note

“His works are simple in design and execution,” a Boston art professor advised students in 1903, “but so full of deep religious feeling that they seem more like those of the early devout masters in this respect.” This sentiment was shared across national borders, and discussions of Marian imagery and symbolism often placed Franz Ittenbach’s Madonnas side by side with their most famous sisters, even Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. By 1898, his fame in this arena was indeed so overwhelming that his first biographer, the Catholic historian and reknowned Spain specialist Heinrich Finke (1855-1938), would title his book Der Madonnenmaler (the painter of Madonnas). That Ittenbach had also participated in some of the era’s most stunning fresco projects—from the widely recognized murals in Remagen’s St. Apollinaris (see Fig. 23) to his altar frescoes in St. Quirinus in the neighboring Neuss—did not change this perception. This was partly due to the fact that Ittenbach created some of his most successful Marian compositions later in his career, after the completion of the ambitious Apollinaris frescoes in 1853. By the fin-de-siècle, Ittenbach was widely regarded as one of the century’s foremost painters of modern devotional art.

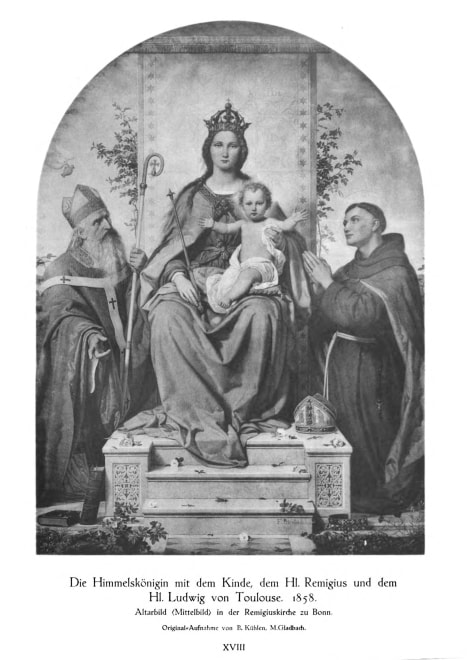

Among his most popular and influential creations was a monumental Queen of Heavenflanked by Saint Remigius and Saint Ludwig which formed the center of a three-partite altar a13th-century Minorite church in Bonn. In 1856, the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen had announced a competition to replace the existing altar of St. Remigius, and Ittenbach was the proud winner. Two years later, he delivered his first major painting after the completion of the Apollinaris murals: a Holy Virgin seated on a white stone throne raised by three steps, with the Christ child on her lap. The insignia of her divine royalty, an elaborate crown and golden scepter with a cross-shaped finial, correspond to the regal aura of her upright posture and the solemn expression of her divine son, who, arms stretched out, reaches out to us in a gesture both welcoming and anticipatory of his future death on the cross. Most viewers, however, did not interpret his pensiveness in such a medieval manner. Instead, their desire for an emotional connection suspended the unmistakable iconographic reference to the Passion, and instead, they characterized the Christ child as “friendly smiling” and “full of desire to take [the viewer] into his outstretched arms.” The same held true for the reading of the Holy Virgin. “The artist has invested the Madonna's features with dignity, but also with kindness and gentleness. On the steps of the altar kneel St. Louis of Toulouse and St. Remigius, the former and the present patron of the church. Especially the former is a perfect type of the saints. The finely thrown garment and the melting harmonious coloring are special merits of the Madonna painting in Bonn.” Adding the two saints and 4 more in the two side panels, Ittenbach expanded his composition into a sacra conversazione (see Fig. 19). Yet for critics and the artist himself, Mary was the ultimate center of the composition and its reception.

Like several of his Marian pictures before, his 1858 Queen of Heaven travelled to France, where she crowned the Salon of 1859. Not everybody was pleased, and Paul Mantz (1821-1895) complained in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts that this Virgin was neither German, neither Italian, neither French, neither Gothic, neither Renaissance, neither modern; “the devout imagery of the Rue Saint-Jacques took hold of this type; art willingly abandoned it to it. // La dévote imageriede la rue Saint-Jacques s'emparera de ce type; l'art le lui abandonne volontiers.” The critic from Le Correspondent, however, disagreed. “Mr. Ittenbach himself is represented,” he announced,“by a large altarpiece of excellent religious feeling, painted on a single plane, like the compositions of Perugino; and he has detached from this painting, to reproduce it separately in a small frame, the head of Saint Louis de Toulouse, of which he has made a study worthy of the brush of our Lesueur.” The public sided with the Correspondent, and two years later, Ittenbach repeated the central motif—now set alone—on the scale of an early Renaissance devotional picture. Hermann Heinrich Becker (1817-1885) was convinced. The painting, the art historiandeclared, is most praiseworthy and—“executed with the greatest care and delicacy” —is a picture “of the most tender loveliness.” Becker’s only criticism was diected at the revival of such an emphatically medieval motif. “We are used to it;” he admitted, “but should not the artists of the later Italian schools have been right when they stripped the representation of the Holy Virginfrom/off these royal insignia and this pomp of worldly splendor?” Of course not, Ittenbach would have answered, with a nod to a Stefan Lochner (c. 1400/1410-1451) or Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441).

With the Saints having stepped aside, Ittenbach had space to indulge his pleasure torender fauna and flora in close-up detail. Inspired by yet another medieval tradition, he placed the throne in a lush garden, thus transforming his trend-setting composition into a Madonna in the Rose Bower (Cat. 6b). The effect is one of great intimacy. It also brings out Ittenbach’s talent to marry the Italian and Northern Renaissance and create a sweet fusion of mellifluous outlines, idealized form, and meticulous nature observation. Once finished, Ittenbach immediately sent his latest “suave et radieuse Vierge” also on tour to France. This time, the Gazette des Beaux-Artswas head over heels. “The Madonna of Monsieur Ittenbach is,” a Monsieur Tainturier reported on September 20, 1860, “one of those jewels we never tire of admiring. This queen of heaven is truly the queen of beauty; seated on a throne enriched with gold and jewels, scepter in hand, she presents to the world her divine son, who, ready to bless, opens his little arms.” And the correspondent, added: “This delightful group, which stands out in full force against the white background of the banner forming the backdrop of the throne, is of a purity of execution that surpasses anything imaginable. // un de ces bijoux qu’on ne saurait se lasser d’admirer. Cette reine des cieux est bien véritablement la reine de beauté; assise sur un trône enrichi d’or et de pierreries, le sceptre en main, elle présente au monde son divin fils, qui, prêt à bénir, entr’ouvre[sic] ses petits bras. Ce groupe délicieux, qui se détache en vigueur sur le fond blanc de la bannière formant le fond du trône, est d’une pureté d’exécution qui surpasse tout ce qu’on peut imaginer.” The art judges of the Exposition universelle de Besançon concurred, and in 1860, the petite Madonna won her maker a much-coveted medal.

But was it indeed our Queen of Heaven who had travelled to France? The answer is not an easy one. Not only do the relevant contemporary catalogues lack measurements or references to the materials used (let alone, illustrations). The title itself also proves too imprecise, and already Ittenbach’s first biographer, Finke, admitted that he could match specific works with all those references to various Himmelsköniginnen born around 1860. In France, moreover, the picture seems to have circulated under two different, if similar title, la reine des cieux and la reine de ciel; yet it cannot be ruled out that either title also referred to yet another replica or variant. The price of “1700 fr.” suggested in the exhibition catalogue of the 1860 show in Besançon certainly puts that “reine des cieux” in the category of a coveted but medium-sizes format on par with a work similar in size and sentiment (and offered by the same consignor), the 1836 Body of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, taken up to Paradise by Angels by another of Schadow’s Düsseldorf students, Karl Mücke (1847–1923). While an identification of that queen of heaven with our design seems most likely, the existence of a second version, put up for sale in by a Belgian collector in 2021, raises the question which of the two had travelled to Besançon. To complicate matters further, both pieces are signed and both pieces have the same date. The only difference is the choice of material for the support, which in the second, minimally smaller version is panel rather than canvas. As both are signed and dated, there can be no doubt that both are by Ittenbach’s hand. If this doubling speaks to the composition’s overwhelming success, it also presents a formidable conundrum. The solution to that riddle might be found in a seal on the back of the version on canvas that French customs had applied to the picture on its way to Paris. Here, it must have been received by an important interlocutor between Düsseldorf and Paris, the publisher August Wilhelm Schulgen (1814-1880). The catalogue entry mentions the Düsseldorf publisher explicitly as consignor, who quite recently, in 1854, had opened a second dependance in Paris. It was located, as the catalogue entry informed future buyers, in the rue Saint-Sulpice. The fact that Schulgen represented all but one of the Prussian artists displayed in Besançon points to his exclusive role in marketing Düsseldorf art in France. How the painting then returned to Germany will be a question for future investigators.

Cat. 6 Figures:

Cat. 6a Franz Ittenbach, Queen of Heaven with the Christ Child, flanked by the Saints Remigius and Ludwig of Toulouse, 1858, oil on canvas, life-size, formerly St. Remigius, Bonn.

Cat. 6b Stefan Lochner, Madonna of the Rose Bower, c. 1440-1442, oil on oak panel, 50.5 x 40 cm, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne