(34 by 47 cm.)

The newly discovered oil sketch now provides important insights into the evolution of Schadow’s last work.

Provenance

Hans Pullem, Düsseldorf (1877-1951)

Private Collection, Germany

Exhibited

Düsseldorf, Ausstellung für christliche Kunst, May 15-October 3, 1909, no. 762

Catalogue note

From the onset, the place of Wilhelm Schadow in the Romantic dominion of Nazarene art was shaped by a quintessentially “Berlin realism,” by a penchant for close nature observation and technical perfection imbibed already in his father’s studio. Fascinated by the coloristic splendor of French Neoclassicism, he adopted the French practice to prepare any history painting (and sometimes even large-scale portraits) with a color sketch for the entire composition in a small format, a practice quite unusual in Germany. In the long run, his integration of French working methods into his practice as both painter and professor set his signature style, the school’s “naturalist idealism,” apart from the aims of his former rebellious comrades, the Lukasbrüder, and cooled off his earlier warm friendship with Overbeck. Regardless of the tension caused by his expectations and embrace of color, Schadow remained indebted to oil studies and the oil sketch as vital preparatory measures, and his last major painting, a Lamentation, was no exception.

Schadow had treated the subject only once before, in 1836, when he painted a Pietà for the Parish Church of the picturesque town of Dülmen, located a good 60 miles Northeast of Düsseldorf (Cat. 12a). It was the second commission he had received from the local art union, the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, and Schadow’s design was accordingly ambitious. Imitating a Gothic window with tracery, the painting depicted Mary at the foot of the cross, her son’s dead body in her arms. The group was flanked by two angels in heavy chasubles, presenting the instruments of Christ’s Passion to the viewer. In a separate field, framed by an arabesque, two putti were holding a scroll upon with a biblical verse inscribed onto it (John 3:16). In typical Schadow fashion, the 1836 Pietà thus couched a complex, thoroughly discursive theological content into a composition made up of a few, static figures where the production of meaning shifted from narrative to iconography. The critics were not convinced. The intellectual rigor and exegetical demands posed by the picture’s symbolism struck them as untimely, and many a viewer reacted with irritation to the angels’ richly decorated robes, which, although common in medieval or Renaissance art, seemed out of place on a modern altar. Maybe Schadow ultimately felt the same way. When he returned to the subject again thirty years later in his last religious work, he approached the topic in an entirely different way, which might have also reflected the changed circumstances of its patronage (Cat. 12b). The 1836 altar had been a major official commission. The lamentation, in contrast, originated with neither patron nor public destination in mind. It followed Schadow’s own advice to find a vessel for the most private feeling in the form of a biblical subject (See Cat. 5). As such, his Mater Dolorosa was an emphatically personal response.

A letter to Julius Hübner confirms this reading. Written in Janury 1860, it is the first mention of the lamentation. “Before my illness, I painted a Mater Dolorosa as my swan song and gave it to the Parish church of St. Andreas,” Schadow writes, “whose priest is my confessor.”The clergyman was Franz Grünmeyer (1802-1871), who had become pastor of Düsseldorf’s St. Andreas in 1841 and finally buried Schadow there in 1862. Style and technique differ considerably from earlier works both in technique and overall mood. Above all, the dark coloration with its gray-black underpainting and likely use of tar mark this as a “late work.” It also demonstrates Schadow’s willingness to learn from his former students. His underpainting harked back to a treatment popular in the Neapolitan Baroque, which Carl Ferdinand Sohn had first brought to Düsseldorf and used with great aplomb in his hit canvas, Two Leonores of 1839 (See Cat. 13). On the basis of these technical observations, I have revised the previouslysuggested date, 1835, in favor of 1853 and thus of a date shortly before Schadow’s deteriorating cataracts—the illness I believe he refers to in the letter to Hübner--left the painter temporarily blind. The uneven execution of the finished altarpiece also points in this direction, as the absenceof Schadow’s characteristic enamel-like surface seems a clear indicator of eyesight problems. On the other hand, this lack of refinement feeds into a greater emotional rawness than in any other of his works. Although emotions remain restrained, Schadow achieved a new oneness of theme, mood and technique. The dark landscape and the subdued, predominantly brownish hues of the garments are surprisingly somber and, drained of color, mirror the figures’ melancholic state of mind. Indeed, the gloomy, threatening evening sky with its dirty, roughly applied swashes of dark blue seems almost like a material manifestation of Schadow’s eschatological concerns. Only the golden yellow of the dresses displayed by the two kneeling women sets a light accent.

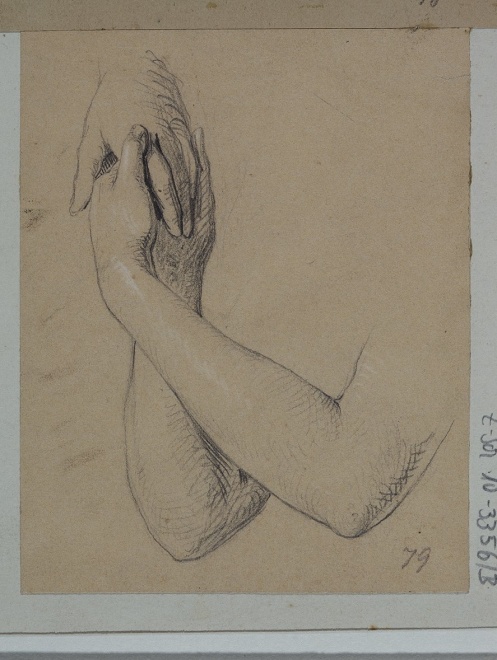

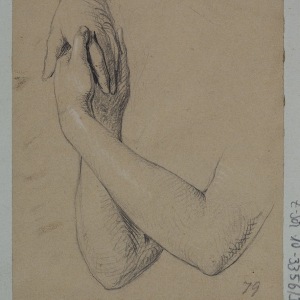

For the second Lamentation, Schadow also experimented with a new composition. Arranging John and the three Marys in a trapezoidal grouping around the central Pietà, he created the illusion of a semi-circular arrangement, which is mirrored and reinforced by the picture’s round arch. At the same time, the overabundant symbolism, which had drawn so much criticism in the first Pietà of 1836 gives way to an appeal to empathic looking. Admittedly, the central figure, Christ’s mother, is still expressionless, her inner composure once again signaling her knowledge of her son’s Passion and its redemptive necessity. The other figures, however, vividly express their grief. As in countless paintings since the Middle Ages, Mary Magdalene, here on the left, embraces Jesus’ feet with despair, her luxuriant hair spilling untamed over her shoulders. Her counterpart on the right gently embraces Jesus’ right hand, kissing its back as if personifying love itself. Schadow attached great importance to the expressivity of this tender, caressing gesture, which he firmed up in a pencil sketch (See Cat. 12c). Despite such greater emphasis, Schadow did not completely renounce traditional symbolism, and he once again added the chalice and crown of thorns as prompts for meditation. Yet as a whole, the hieratic structure of the Dülmen altarpiece has yielded to a much more emotional approach that replaces a ceremonial with a spiritualized effect.

The newly discovered oil sketch now provides important insights into the evolution of Schadow’s last work. While the sketch prefigures the composition for the most part, there are some noteworthy differences. The most obvious is the color scheme, which is noticeable brighter and more saturated that in the final painting, which suggests dating it closer to the 1848 Fons Vitae. This opens up the question whether Schadow’s abilities simply had weakened, or the tar has leaked through the surface layer of paint, or whether that surface is in dire need of cleaning (or all of the above). The other notable difference is the position of Christ’s head, which falls further back, the hair here blond and the halo fashioned more clearly after the Italian old masters. If these deviations already point to an authorship by Schadow, the final proof for a secure attribution can be found in a pencil sketch, now housed in the Landesmuseum Hannover, which prepared the Pietà-motif at the composition’s center (See Cat. 12d). In a future revised edition of my catalogue raisonné (Grewe 2017), the oil sketch of the Lamentation would thus be included as an authentic work by Schadow.

Cat. No. 12 Figures

Cat. no. 12a Wilhelm Schadow, Lamentation, 1853, oil on canvas, 161 x 214 cm, St. Andreas, Düsseldorf

Cat. no. 12b August Hoffmann, after Wilhelm Schadow, Pietà (or Lamentation), 1838, copper engraving, 45.5 x 29.8 cm (plate), Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf

Cat. no. 12c Wilhelm Schadow, Study of Two Arms, circa 1848-1850, Pencil, heightened with white chalk, 10,7 x 8,6 cm, Düsseldorf, Künstlerverein Malkasten

Cat. no. 12d Wilhelm Schadow, Pietà, c. 1850, Black chalk, sepia, heightened with white ink, on light brown clay paper, 28,7 x 26,8 cm, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Hannover