Further images

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

-

View larger version of this thumbnail image.

Provenance

Artist

Thence by descent to his daughter, Mrs Sophie Hasenclever

Gerda Fein, Heidelberg

Sale, Sotheby’s Munich, 3 December 1996, lot 26.

Sale, Van Ham Auktionshaus, Cologne, 30 June 2001, lot 1643

Sale, Auktionshaus Neumeister, Munich, 20 March 2002, lot 779

Sale, Auktionshaus Leo Spik, Berlin, 16 June 2005, lot 216

Sale, Dorotheum, Vienna, 13 March 2013, lot 231

Private collection, California (acquired at the above sale)Literature

Cordula Grewe, Wilhelm Schadow (1788-1862), Monographie und Catalogue Raisonné, Dissertation, Freiburg, 1998, vol. II, no. 43.8, p. 100; re-used, see no. 44.4a, p.105

Cordula Grewe, Wilhelm Schadow: Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde. Mit einer Auswahl der

dazugehörigen Zeichnungen und Druckgraphiken, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017, no. 64.4, pp.318, p.139, ill. p.140 (also used for no. 65).

Catalogue note

In 1839, thirteen years after he had assumed the directorship of the Düsseldorf academy, Wilhelm Schadow (1788-1862) embarked on the third and last sojourn to his beloved Italy. By this time, the golden age of what the poet Karl Leberecht Immermann (1796-1840) had once called Düsseldorf's Beginnings had come to an end. The era’s political unrest, confessional conflicts and economic crisis had not stopped before the gates of the academy, and by mid-century, the international popularity of the now famous Düsseldorf School of Painting had turned into a curse. The more the academy expanded, the harder the struggle to secure resources, market share or even a space in the art program, and most blamed Schadow. The director himself was extremely concerned and noticed that even his most famous students had hardly any sufficient commissions. Susceptible to depression from a young age onward, Schadow did not take the increasing attacks on his leadership and intensifying critique of his artistic guidance lightly. His capacity to work and level of productivity declined, a situation worsened by the onset of serious health problems. When Schadow returned from Italy in 1840, the mood in Düsseldorf’s art scenehad changed, and not for the better. But Schadow did not give up.

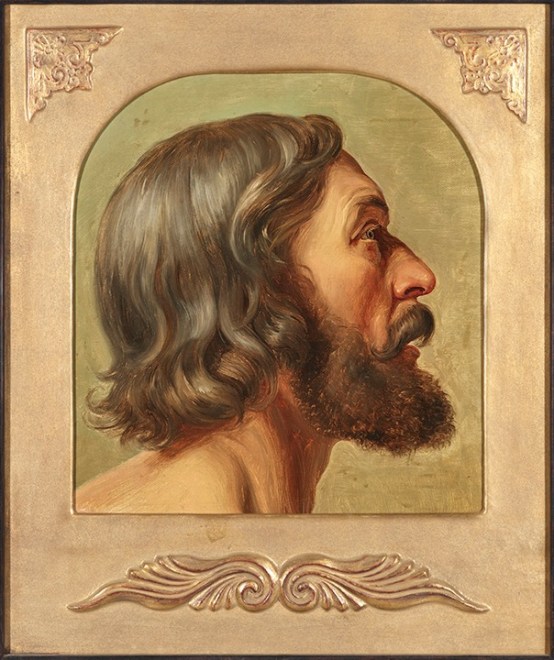

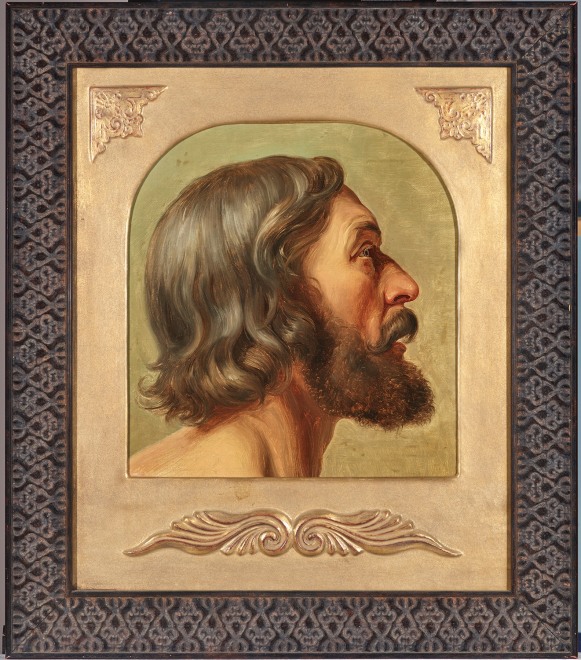

On the contrary, in this moment of crisis, he embarked on some of his most ambitious projects and he could count on his most prominent patrons. Gleefully, he noted in January 1845that the king did not head any negative judgment about his abilities and “has ordered a large picture from me for the Berlin Museum.” The monumental painting, an allegorical Fons Vitae (fountain of life) and the largest single canvas Schadow ever produced, was intended for the Neue Museum, the latest of the capital’s new exhibition halls and once more designed by Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865). When Schadow received the commission, the building was still under construction (1841-1855). In step with the commission’s prestige, Schadow took pains with the project’s preparation (Cat. 11a). Once he had worked out the basic composition, he produced a series of meticulous studies for the bodies, draperies, and elaborate costumes. Additionally, he was interested in the figures’ pantomimic eloquence, drawing many in the nude, as well as their psychological expressivity. To that end Schadow executed numerous portraits in pencil and, as in the case of the bearded man, in oil. Paying close attention to the texture of his model’s facial hair and rich head of graying locks, which bounce energetically off the shoulder, Schadow indulged in a much looser, impasto brushwork than in the finely worked surfaces of his finished paintings. At the same time, the reduced palette of grays and browns catered to his preoccupation with the allure of age and experience both firmly inscribed in the man’s tanned skin and intense, somewhat strained look. The complexity of that expression, which hoversbetween amazement and anxiety, pleading and disbelief, underscores the important role of physiognomic realism and psychological penetration for Schadow’s approach to history painting. The painter was clearly satisfied with his efforts, so satisfied indeed that he immediately reused the study in his next major project, the triptych Purgatorium, Paradise, Hell (1848-1852). While the bearded man thus first joined the pilgrims in the 1848 Fons Vitae, kneeling in the foreground on the left (Cat. 11b), he returned only shortly afterwards as a stately prince in the Purgatorium(Cat. 11c).

While the portrait of the bearded man might simply confirm Schadow’s overall working method, the existence of a second, almost identical study of the same bearded man but from a different hand is noteworthy (Cat. 11d).. The two versions draw attention to an important practice in Düsseldorf: the joint study of models and subsumption of individual surface treatment under a homogeneous school-style. In 1832, the artists demonstrated their exceptional aesthetic, technical and ideological unity in a group portrait in which each had portrayed the other but aimed at a perfect visual oneness of hands (Cat. 11e). The result stunned their contemporaries who nicknamed the painting programmatically The Schadow Circle. Of course, one inevitable upshot of this practice was a notable difficulty to distinguish hands, and this applies to the two oil sketches at hand as well. For a long time, the head now in the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf was attributed to Schadow; however, when the study presented here surfaced on the art market in the 1990s this attribution needed to be revised in favor of attributing this version to Schadow.

Cat. 11 Figures:

Cat. 11a Wilhelm Schadow, Fons Vitae, 1848, pen in gray-brown, 53,7 x 41,3 cm, Lübeck, Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus

Cat. 11b Wilhelm Schadow, A Pilgrim Kneeling at the Fountain of Life, detail from the FonsVitae, 1848, oil on canvas, 452 x 335 cm, SPSG, Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam

Cat. 11c Wilhelm Schadow, Figure of a Prince, detail from the Purgatorium, 1848–1852, oil on canvas, 241.5 x 303, Museum Kunstpalast (on permanent loan from the State of North Rhine-Westphalia / Administration of Justice, Düsseldorf

Cat. 11d Wilhelm Schadow (?), Study of a Bearded Man, oil on canvas, 42.2 x 33.5 cm, Museum Kunstpalast (Collection of the Düsseldorf Art Academy), Düsseldorf

Cat. No. 11e Julius Hübner d. Ä. in cooperation with Wilhelm Schadow, Carl Ferdinand Sohn, Eduard Bendemann and Theodor Hildebrandt. The Bendemann Family and Friends (also knownas The Schadow Circle), 1832, oil on canvas, 108 x 175 cm, Kunstmuseen Krefeld