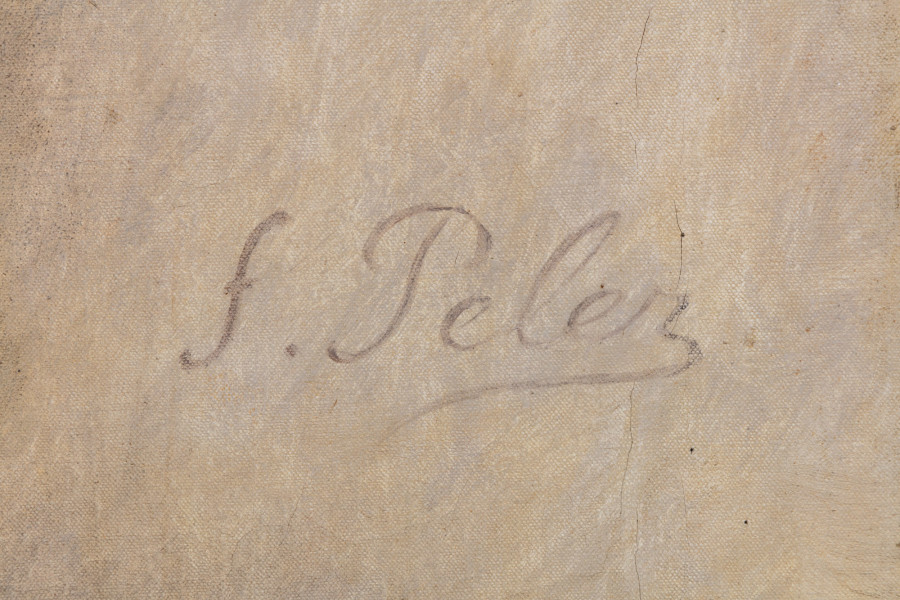

Dressed in an over-sized adult coat, Young Street Urchin is a study for La Vachalcade (Petit Palais, Paris), one of Pelez’s most provocative and mysterious paintings.

Provenance

Jean-Claude Brialy, France

Catalogue note

Dressed in an over-sized adult coat, Young Street Urchin is a study for La Vachalcade (Petit Palais, Paris), one of Pelez’s most provocative and mysterious paintings. This large-scale work (it measures 188 by 245 cm.) was never exhibited publicly and remained in Pelez’s studio following his death. Studies for the individual children, painted on the same scale as the final work, appear in a photograph of the studio in 1913. The location of these studies has remained unknown, which makes the appearance of our painting an exciting discovery.

The Vachalcade was a carnival first held in Montmartre in February 1896. It featured a procession, parade and floats and was created to provide a charitable fund for artists living in poverty. This event was the inspiration for Pelez’s painting, and his interpretation corresponds to many of his best-known works, which treated street children as the primary subjects. As so aptly described by the late Linda Nochlin, “The Vachalcade features the same little lemon-selling street urchin in a man-sized jacket amid a crowd of weirdly masked figures to the right and other vagrant children to the left, one in a Pierrot costume, smiling broadly against a banner bearing the inscription Misère, from which a dead rat dangles. The implications of the composition are both obvious and mysterious. What is clear is the misery lies at the heart of the image, signified by the over-sized jacket and hat of the poor boy at the center of the canvas and made explicit by the word emblazoned on the banner. The fact that two of the street urchins are wearing over-sized clothing, clearly meant for grown men, not children, adds to the pathos of the representation, while the masks of the revelers to the right specify its grotesquery.” (Linda Nochlin, Misère: The Visual Representation of Misery in the 19th Century, London, 2018, p. 143).

La Valchalcade, and our study for the central figure of the young boy, mark a stylistic shift in Pelez’s work at this time. Beginning in the late 1890s, he leaves behind the Academic rigor learned in the studio of Alexandre Cabanel and apparent in earlier works such as his Grimaces et Misère from 1888, in favor of a style that could more accurately be described as a fresco technique. From here on his palette becomes softer and diffused, as if being viewed through a thin veil; one may even say it starts to border on Symbolism. Young Street Urchin announces this new phase for Pelez. Set against an empty background and painted in a limited palette of neutral brown tones, he silently speaks his own narrative; this little street urchin is the precursor, with a shared humanity and an inevitable fate, to Pelez’s cartoons of homeless men standing in a breadline for the great La Bouchée de pain of 1908.