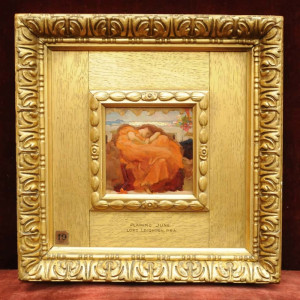

11.4 by 11 cm.

Flaming June is among the most famous masterpieces of the nineteenth century. In the present study we see the moment the masterpeice was fully conceptualized.

Provenance

Sir George Henschel (1850-1934), Bedford Gardens, London (acquired directly from the artist and sold, Christie’s, London, July 14, 1916, lot 15)William Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851-1925) (acquired at the above sale through Gooden & Fox)

Sale: The Leverhulme Collection, Sotheby’s, Thornton Manor, Mereyside, June 26-28, 2001, lot 401, illustrated

Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox, London

John Schaeffer, Sydney (acquired from the above)

Acquired from the above

Exhibited

Springville (Utah) Museum of Art, The John H. Schaeffer collection of Victorian and European art, August 26, 2009-February 28, 2010London, Leighton House Museum, on loan March-May 2010

Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Victorian Visions: Nineteenth-Century Art from the John Schaeffer Collection, May 20-August 29, 2010, no. 29

New York, The Frick Collection, Leighton’s Flaming June, June 9, 2015-September 6, 2015

London, Leighton House museum, Flaming June: The Making of an Icon, November 4 2016 - April 2 2017

Literature

“George Henschel,” Musical Times, March 1, 1900, p. 159Leonée and Richard Ormond, Lord Leighton, New Haven and London, 1975, p. 173, no. 389

Antique Trade Gazette, July 4, 2001, p. 1, illustrated

Burlington Magazine, vol. 145, no. 1206, September 2003, illustrated n.p.

Catalogue note

Frederic Leighton’s most iconic painting, Flaming June, is a testament to the aesthetic and philosophical interests of an artist with investments in both academic classicism and the avant-garde. His refined technique, traditional process, and intellectual subject matter set him apart from many of his contemporaries, and yet his commitment to the ideal of “art for art’s sake” and pursuit of beauty as the true value in art align him with some of the most progressive artists of the period.

Painted and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1895, Flaming June (see secondary image above) belongs to a group of late works featuring idealized female figures: robust and sensual women cast as sibyls, muses, or nymphs. Specifically, it is an evocation of one of Michelangelo’s most erotic images, Leda and the Swan of 1529. A beautiful young woman in a vivid orange gown is seated in profile. Asleep, the configuration of her body is visible through the lush, transparent drapery, conveying a sense of her physical presence and sexuality. Resembling a bas-relief, she is positioned within a spare classical setting, including a marble terrace, bouquet of oleanders, and decorative awning bordering the suggestion of the sea in the distance.

In addition to Renaissance sources for the figure, comparisons have been made to the sleeping women of Edward Burne-Jones’ Briar Rose paintings, executed between 1873 and 1890 (Buscot Park, Oxfordshire), George Frederic Watts’ allegorical representation of Hope (various versions, including one at the Watts Gallery, Compton), and The Dreamers by Albert Moore (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery). The classically inspired architectural setting and other components of the painting can be likened to Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s paintings from 1880 onward, such as Sappho and Alcaeus (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore). Because Leighton was a cosmopolitan and literate individual, the painting might also be read in relation to themes and symbols of Victorian literature. In Victorian poetry, sleep is often suggestive of death, while oleanders are symbolic of danger, and these associations add to the enduring allure and mystery.

While there is no definitive interpretation for this masterpiece, Leighton’s creative process is well documented: beginning with an idea, he then developed the pose, format, and composition through meticulous studies of a live model, and determined the palette in oil sketches. In 1890, the art critic Gertrude Campbell praised Leighton’s careful methodology: “A picture by him is but the last stage of a long and laborious artistic process, a building up bit by bit of the whole composition in every detail” (as quoted in Susan Grace Galassi and Pablo Pérez d’Ors, Leighton’s Flaming June, exh. cat., New York, 2015, p. 29). The present study highlights Leighton’s mastery of drawing and design: here he established the color harmony and refined the composition, working through the most significant aspects of the final image.