99.06 by 51.12 cm.

“The aim of art is to glorify beauty.”

—Alphonse Mucha

Literature

Catalog: Rennert/Weill 18 var. 1; Bridges P3-P6.

Arthur Ellridge, Mucha: The Triumph of Art Nouveau, Terrail, Paris, 1992, pp. 75-78 (ill.)

Victor Arwas/Jana Brabcova-Orilikova/Anna Dvorak, The Spirit of Art Nouveau, Art Services International, Alexandria, Virginia, 1998, nos. 44a-44d, pp. 186=187 (ill.)

Sarah Mucha, Alphonse Mucha: Celebration the Creation of the Mucha Museum, Prague,

Malcom Saunders Publishing Ltd., London, 2000, pp. 34-35 (ill.)

Catalogue note

Alphonse Mucha leapt to fame with the overnight success of his commercial poster for the internationally celebrated actress, Sarah Bernhardt. The nearly life-sized likeness of the fêted tragic actress caused a sensation when it debuted on Parisian streets in 1895, initiating a flood of commissions for the young graphic artist. In the glittering, decadent world of the Belle Époque, Mucha’s inescapable calligraphic lines and mesmeric female figures sold nearly everything there was to sell, from Job cigarettes to Waverly bicycles and Möet & Chandon champagne.

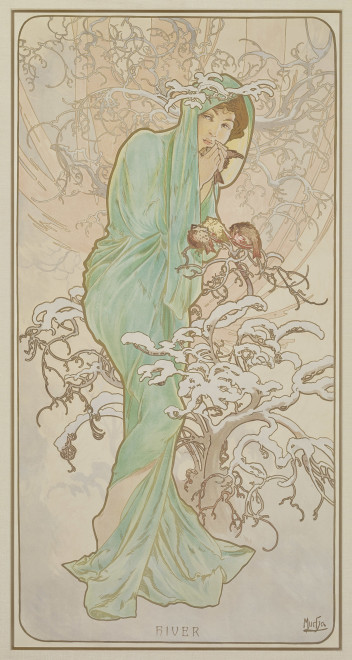

However, Mucha resisted relegation to the ranks of a superficial commercial illustrator and considered himself an artist first and foremost. In 1896 he created The Seasons, his first design for a decorative ensemble of artistic lithographs. In this iconic series, an impression from the first variant of the original published version here, Mucha’s nymph-like women are set within seasonal views of the countryside and embody the mood of each stage in the natural cycle. Innocent and fair Spring is followed by sultry and beguiling Summer, then fruitful and abundant Autumn, and frosty and reclusive Winter. While the trope of personifying the seasons was nothing new—it had been used by Old Master painters and contemporary artists alike—Mucha transformed the motif to speak the language of the modern (and often overwhelming) world of the late nineteenth century. This design proved so popular that the elite Parisian printer Fernand Champenois requested that Mucha create at least two more based on the theme in 1897 and 1900.

By the 1890s, colorful lithographic prints had skyrocketed to the status of popular icons. Technological advances rendered large and boldly colored prints widely accessible and imminently reproducible, generating a phenomenon known as affichomanie, or “poster mania.” Audiences thronged to view them on boulevards—a spectacle likened to gallery openings in a “salon of the street”—and they were coveted by collectors for decoration in private homes. By 1896, Mucha’s works were featured at the independent Salon des Cent poster exhibition on the Rue Bonaparte, and the following year a major retrospective of his work travelled to Vienna, Prague, Munich, Brussels, London, and New York, confirming his international reputation as the “master of the poster.” He later reflected on this golden age of graphic art, recalling, “I was happy to be involved in an art for the people…It was inexpensive, accessible to the general public, and it found a home with middle-class families as well as in more affluent circles.”

Yet Mucha’s subject matter distinguishes him from other graphic artists such as Henri Toulouse Lautrec and Jules Chéret who represented the disorienting dynamism of modern figures in the boulevard or the dance hall. Rather, Mucha’s women are timeless types who have retreated to the rhythms of nature, existing in essential harmony with their environment. Summer, for instance, sacrifices individuated details to all-encompassing, corresponding effect—her headdress of poppies and brunette tendrils toppling effortlessly into the writhing grapevines encasing her in the palpable weight of thick, late-summer heat. Such imagery could create a soothing, enduringly beautiful antidote to the effects of the dizzyingly, fast-paced industrial metropolis for a population and that was, in the words of Émile Zola, “wracked by a nervous irritability… (and) sick and tired of progress.” Works such as these were therefore equated with the organic, interiorized decorative spirit transforming Parisian homes into aesthetic asylums of retreat. While we now remember this style as the “Art Nouveau,” contemporary critics knew it by a more familiar name: le style Mucha.