Provenance

Studio of the artist

Thence by descent

Exhibited

Paris, Salon of 1844, no. 230

Rouen, Exposition de 1847, Musée de Rouen, no. 77

Versailles, Hôtel de ville, Exposition annuelle de la Société des amis des art de Seine et Oise, November 1860

Literature

Desbarrolles, Ad., "Lettre sur le Salon de 1844," Bulletin des amis des arts, t.II, 1844, p.249"Le Salon," Journal des artistes, 2nd series, vol. 1, 2 June 1844, p.82-83

Coursiers, Th., "Revue artistique," Journal des artistes, vol. 4, 1847, p.140

Delcourt, A., Visites au musée de Rouen, revue de l’exposition de 1847, Rouen, 1847, p. 20

A.D., "Causerie artistique," La Lumière, no. 49, 8 December 1860, p.195

Renaud, A., "Le Salon de 1860 à Versailles," Les Beaux-arts: revue de l'art ancien et moderne, Volume 1, 15 April-15 December 1860, p. 494

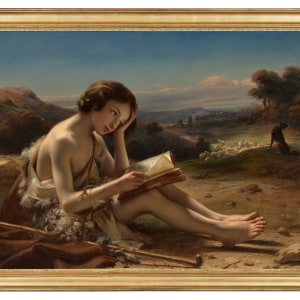

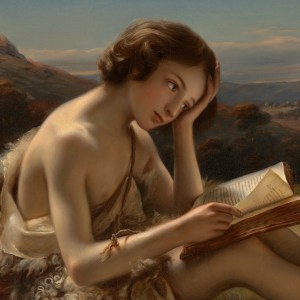

Catalogue note

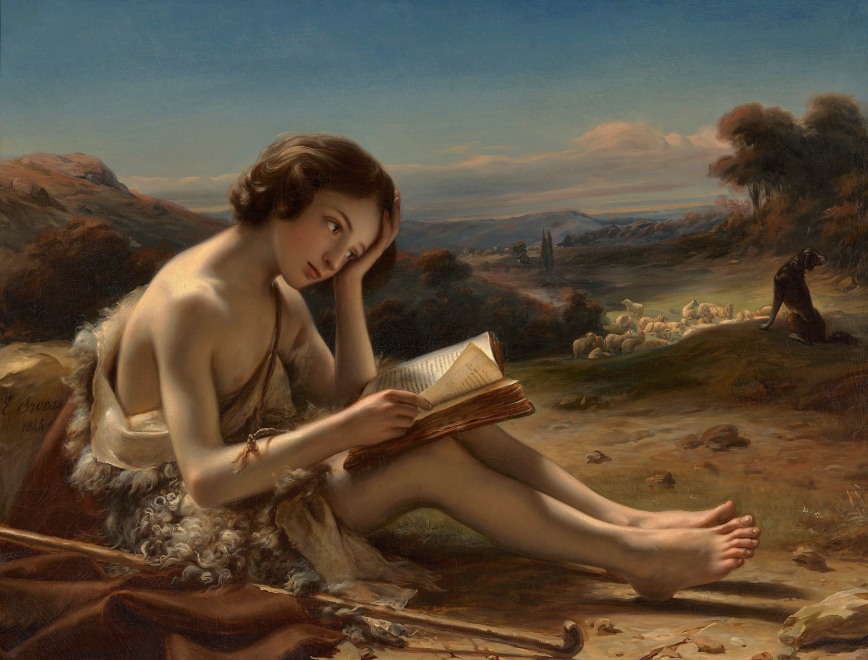

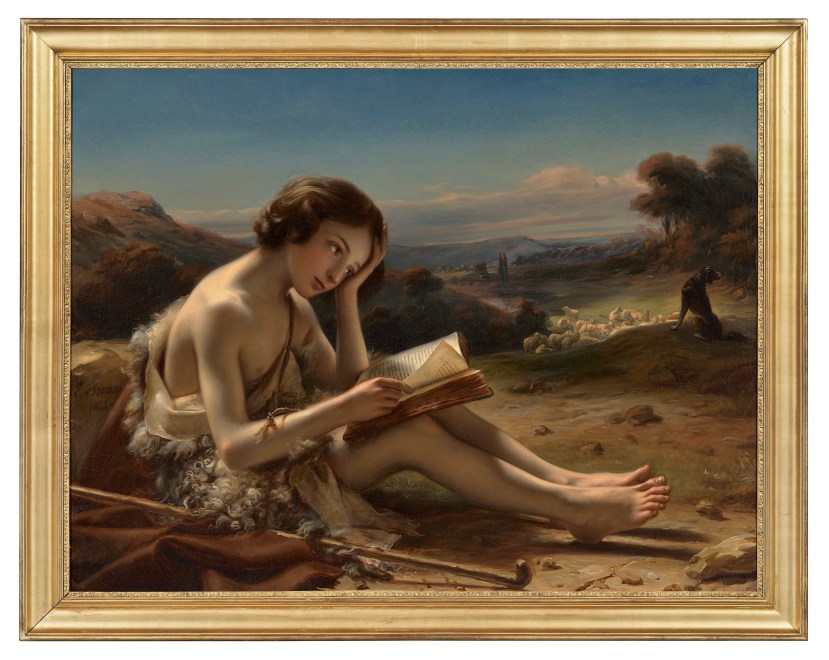

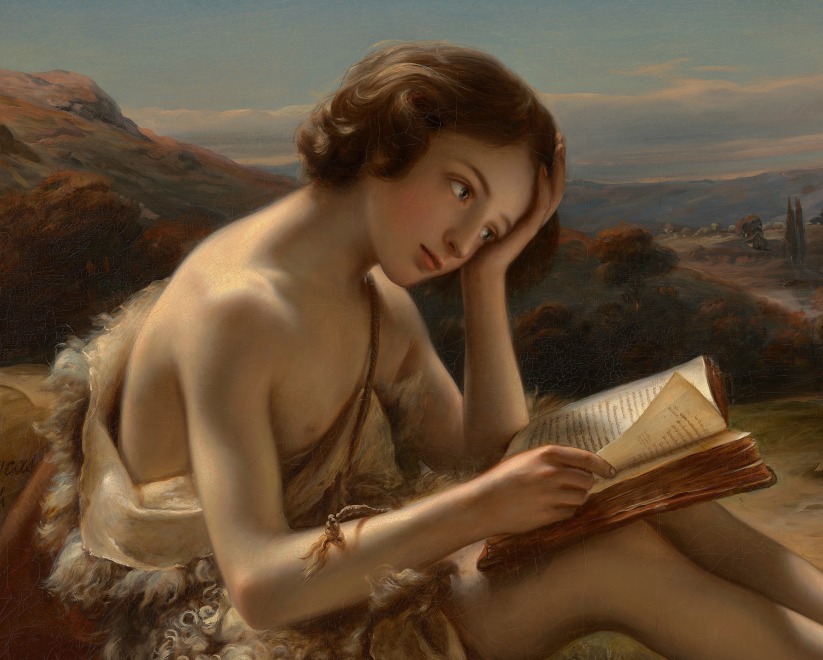

At first glance, the subject of Eugène-Méry Brocas’s painting appears to evoke the iconography of a young St. John the Baptist. As recorded in the Gospel of Luke “the child grew and became strong in spirit; and he lived in the wilderness ….” Luke I:80. Brocas has included motifs traditionally associated with St. John the Baptist, such as the animal skin tunic and the staff, and if we wanted to be speculative, we might hypothesize that the young shepherd is reading a symbolic version of the Gospel of Luke. Luckily, our painting was Brocas’s entry to the 1844 Salon and we therefore have a title: The Childhood of Valentin Jameray-Duval (Jeunesse de Valentin Jameray-Duval). Far from a household name and an even more esoteric choice for a Salon painting, the biography of Valentin Jameray-Duval (1695-1775) reads like a folk tale, or a story worthy of Charles Dickens. Fortunately, Jameray-Duval recorded his life story in his mémoires, which have been edited in 1860 (Anne Manning) and more recently in 1981 (Jean-Marie Goulemot).

Born in Champagne in 1695 to an impoverished family and orphaned at the age of ten, Valentin set out on his own at a time when France was ravaged by war and famine. In his Mémoires He recounts details of how he survived the severe winter of 1706, wandering from one farmhouse to another in search of bread, and his miraculous recovery from a severe illness that brought him to the brink of death. When his health finally returned, he travelled from village to village and was eventually taken in by a hermit, Brother Palemon. To earn his keep, he tended to the farm animals at the hermitage while he learned to read, developing a passion for books; this is the subject of our painting. Valentin’s scholarly bent also extended to an interest in maps, and according to his Mémoires, he was discovered, seated by a large tree in the forest with his maps and charts scattered around him by the two young princes of Lorraine. This encounter led to Duke Leopold of Lorraine sponsoring Valentin’s education with the Jesuits of Pont-a-Mousson. In 1718, the Duke took him to Paris where he was appointed librarian and professor of history at the Academy of Luneville. Valentin eventually became librarian to the Grand Duke of Tuscany (Duke Francis Stephen of Lorraine) at the Pitti Palace in Florence, followed by overseeing the collection of coins and medals for the Grand Duke in Vienna.

This rags to riches story of Valentin Jameray Duval’s life was first published in his Mémoires in 1784 and 1785 and provided the inspiration and source for Brocas’s painting. The Mémoires describe a multitude of vivid details of Valentin’s journey from impoverished orphan to librarian at the Pitti Palace, any of which could have provided a suitable theme for a Salon painting. Very little biographical information exists for the artist, Eugène-Méry Brocas, therefore understanding the context for this painting, and especially the choice of such a unique subject is a matter of some speculation. Interestingly, there may be some parallels between Valentin Jameray Duval and one of France’s greatest landscape painters, Claude Lorrain. One cannot help but compare the rolling hills, distant mountains and diffused pink clouds in Brocas’s painting to the luminosity and pure poetry so often found in Claude’s landscapes. The life story of Claude is not dissimilar to Brocas’s protagonist, Valentin. Both had ties to the Duchy of Lorraine, both came from humble origins and were ill-educated but innately gifted, and both went to Italy and became hugely successful in their chosen métiers. Valentin read his books and studied his maps out-of-doors while working as a young herdsman and Claude “tried by every means to penetrate nature, lying in the fields before the break of day and until night in order to learn to represent very exactly the red morning sky, sunrise and sunset and the evening hours.” (quoted in K. Baetjer. “Claude Lorrain (1604/5?-1682)” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 2014). The parallels of the two lives, while interesting, may simply be coincidental; however the landscape in Brocas’s painting is clearly an homage to Claude, while Valentin’s youthful physique, with its modelled and polished surface, has its origins in the ideal beauty of Neo-classicism and to the delicate features of Canova’s Cupid.