Provenance

Sale: Sotheby's, New York, 5 May 1999, lot 256

Edward T. Wilson, Fund for Fine Arts, Inc., Bethesda, Maryland

Wendy Goldsmith Ltd., London, 2003

Private collection, California, USA, 2003 (acquired from the above)

Exhibited

New York, Dahesh Museum of Art, Charle Bargue: The Art of Drawing, November 25, 2003 - February 8, 2004, Paris, ACR Edition, 2003, no. 20

Literature

Gerald M. Ackerman, with the collaboration of Graydon Parrish, Charles Bargue

with the collaboration of Jean-Leon Gérôme, Drawing Course, ACR edition, 2003, no. 20B, p. 290

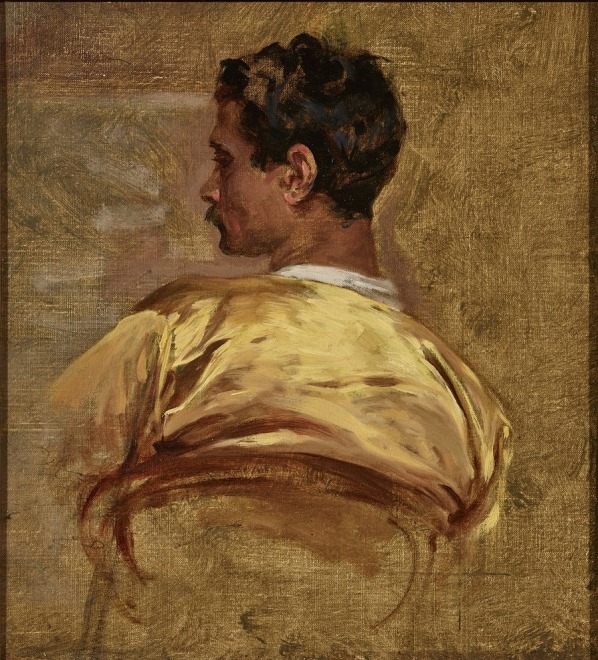

Catalogue note

This étude, or study, is one of a series of single-figure paintings by Charles Bargue, and one of many of his portraits that feature a figure seen from the back. Bargue may have been inspired to adopt this unusual view by his colleague Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), with whom he worked for a number of years both in the studio and as the co-author of one of the nineteenth-century’s most popular and effective drawing manuals, the Cours de dessin, published by Goupil & Cie. between 1866 and 1871.

Little is known about Bargue’s early life. His close relationship with Gérôme has led to some confusion about aspects of his biography, as well as about the authorship of several paintings that share a common theme. A label on the verso of one image (fig. 1), written by Gérôme and featuring one of his favorite Orientalist subjects, relates directly to this point: “I, the undersigned, declare that the picture representing Bashi-Bazouks playing chess, measuring .90 in height and .70 in width, is by M. Bargue. I can, moreover, even testify that I saw him do it, and that I loaned him some costumes and headdresses for its execution. – J.-L. Gérôme, Member of the Institute.”

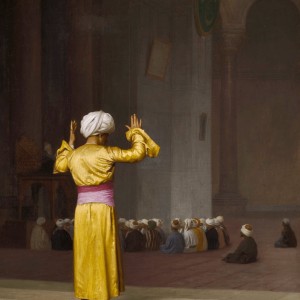

The present oil sketch is remarkable for the brilliant yellow of the man’s jacket, which echoes Gérôme’s distinctive palette and again raises the question of one artist’s influence on the other. Indeed, in a painting of an Arab figure at prayer, Gérôme includes both this vivid color and the backside view (fig. 2). The latter conceit was not popular with his dealer, and Gérôme was taken to task. As the artist explained, “Prayer in the Mosque had been reserved by Monsieur Simon and I remember that he made me put a figure facing the spectator, by saying that since all the others were seen from the back or in profile, it would not sell. I did as he wanted because his reasons were commercially sound,” (Letter to [his dealer] Knoedler, 8 June 1903, Custodia foundation, Fritz Lugt collection, Netherlands Institute, Paris).

Bargue’s unfinished painting – one of only approximately twenty oils in his oeuvre – exhibits all the best attributes of his style, which were recognized by contemporary critics. As the prolific American writer Edward Strahan (1838-1886) penned in his History of French Painting, Bargue’s finest compositions possessed “a unity and completeness of effect enriched with a wondrous detail, from this arises the rare value of his works which, like some of Meisonnier’s, command literally more than their weight in gold,” (Edward Strahan, A History of French Painting, New York, 1888, p. 321). Bargue’s facility with color, and his ability to reduce a figure to their essentials, defining structure and even character with a few clever strokes, is in abundant evidence here. These qualities have led to a revival of interest in Bargue, and an escalation in the price and desirability of his works.

This note was written by Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D.

Figure 1: Charles Bargue, Bashi Bazouks Playing Chess, ca. 1883, oil on panel, 35 x 27 ½ in. (88.9 x 69.9 cm), Malden Public Library, Massachusetts.

Figure 2: Jean-Léon Gérôme, Prière dans la mosquée, oil on canvas, 16 1/8 by 13 in. (41 by 33 cm), Private Collection.