Provenance

Commissioned to the artist by Simon Moritz Bethmann for Louise de Bethmann, 1823

Private collection, Switzerland

Sale, Beurret & Bailly Auktionen, Basel, 21 June 2017, lot 28

Private collection, California (acquired at the above sale)Literature

Wilhelm Schadow, 1861, “Jugenderinnerungen,“ Kölnische Zeitung, 28 August-17 September 1891, no 752 (sept. 16)

Heinz Peters, “Wilhelm von Schadow,“ in Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein, no. 164, 1962, p. 66

Heinrich Schmidt, Wilhelm von Schadow zum hundertsten Todestag, Neuss, Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, 1962, p.23

Cordula Grewe, Wilhelm Schadow (1788-1862), Monographie und Catalogue Raisonné, Dissertation, Freiburg, 1998, vol II, no. 17, p. 38

Cordula Grewe, Wilhelm Schadow: Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde. Mit einer Auswahl der

dazugehörigen Zeichnungen und Druckgraphiken, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017, no. 25, pp. 59, ill., p.60, p. 302

Catalogue note

In 1823, Count Alexei Araktschejew (1769-1834), then the Russian war minister, approached Wilhelm Schadow (1788-1862) with the request to paint the Prussian King Frederick William III. Well-received, it attracted further commissions, several by prominent patrons. The painter was pleased. “In addition to many portraits,” he noted in his memoirs, “I executed some Christian representations, such as a Madonna for the Banquier Bethmann and a second for the Grand Duke of Weimar, which is in the castle there,” and a third for the Bishop of Ermland (a historic region in East Prussian, also known as Warmia, and today located in Poland). Most of these paintings are missing today, with little written evidence of what they looked like. The exception is a picture described as a Madonna, a half-figure in life size, which Schadow had submitted to the art exhibition of the Berlin Academy in 1822. In June of the following year, a lengthy review by Amalie von Helwig (1776-1831) appeared in Schorn’s influential Kunst-Blatt. The picture shows, the widely-read art critic told her readers, “the virginal mother walking in an open serene area, as she softly and tenderly kisses the child in her arms on the forehead. The expression of the mother’s head is very lovely, the carnation warm and clear, the drapery tasteful, in strong colors edged with fine ornaments in gold, reminiscent of the best achievements of this kind … .” As far as the execution was concerned, Helwig concluded, the picture embodied a further progress in Schadow’s artistic conception. “If we are not mistaken, the artist’s taste has been further perfected with regard to the drapery, which … seems so well understood as to be magnificently ordered.” Even the painter and art historian Ernst Förster (1800-1885), who usually championed Peter Cornelius (1783-1867), was swayed. Schadow’s Mary with Child, he gushed, was “of the most wonderful expression, a beautiful, true picture of the most intimate motherly tenderness.”

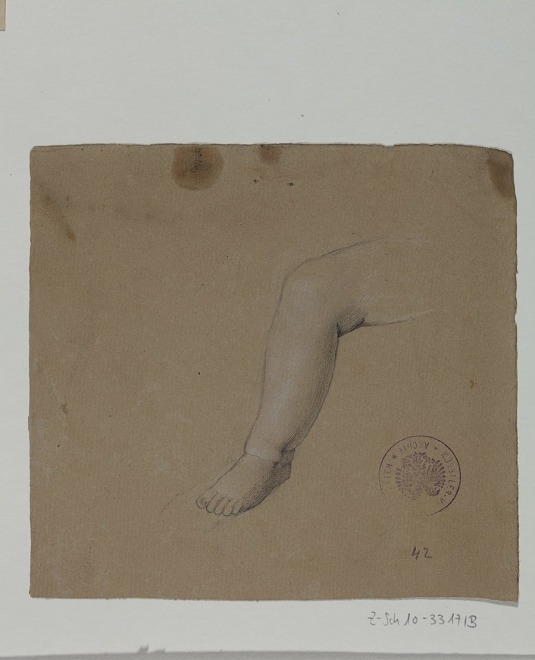

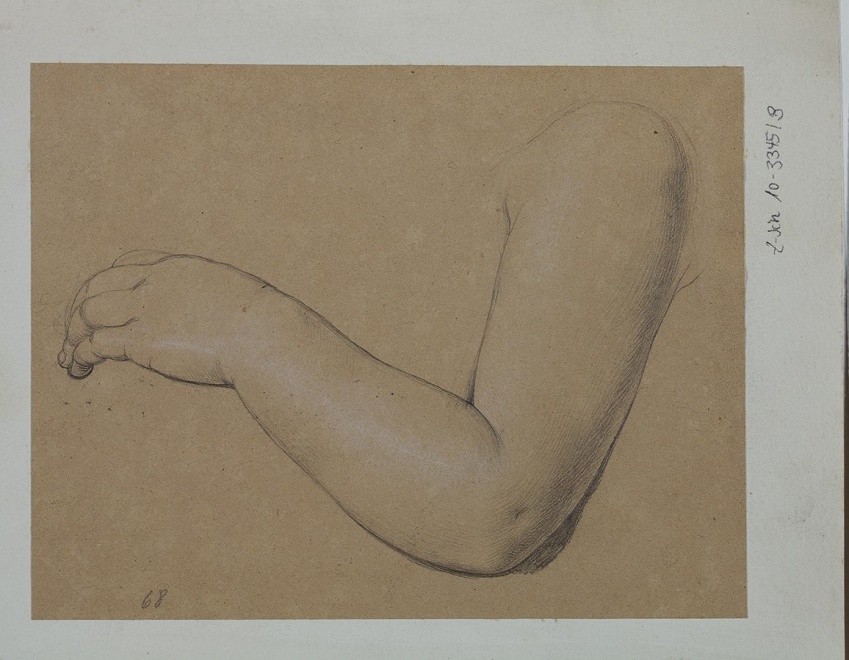

The descriptions correspond faithfully to the small-scale canvas, which resurfaced on the Swiss art market in the summer of 2017, and possesses precisely the intimate tenderness cherished so much by Helwig. Two pencil drawings substantiate this attribution. Housed today in the Künstlerverein Malkasten, Düsseldorf, they show a toddler’s left arm and left leg respectively (Cats. 10a and 10b). Moreover, the picture’s exquisite execution, too, points to Schadow's authorship while the particular format and rather summarily applied paint (esp. in sections of the landscape and garment) suggest a replica by the artist’s own hand. The smaller format certainly befits the subject matter. It creates a sense of intimacy, which, uniting motif and color choices, makes Maria, kissing the Christ Child a true little gem.

This assumption of Schadow’s authorship is supported by two inscriptions on the back that allow us to connect the picture to a concrete written reference: “Louise de Bethmann / 1823” in pen on the upper stretcher; “Schadow” in pencil on the lower. Together, these inscriptions identify the painting as the hitherto lost “Bethmann Madonna.” The exact circumstances of the commission must be speculation, but not so the identity of the patron, the “Banquier Bethmann,” who unquestionably was Simon Moritz von Bethmann (1768-1826). The Frankfurt banker had married Louise Friederike Boode (1792-1869), a native Dutch woman, in 1810. The couple had four sons--Moritz, Karl, Alexander and Heinrich--the eldest of whom, Moritz, would take over the bank’s management after his father's unexpected early death. The family business, the so-called “Bethmann Brothers Bank,” had emerged from the 18th century as one of the richest and most influential banking institutions in Germany. In 1806 Emperor Franz I. had elevated the family into nobility with the family's right to pass on the noble title from generation to generation. Not surprisingly, the Bethmanns played an important role in Frankfurt, both culturally and politically, and Simon Moritz made a name for himself not least by sponsoring the Philanthropin (Greek for “place of humanity”) a Jewish elementary and high school for Frankfurt’s Jewry founded by Mayer Amschel Rothchild in 1804. Bethmann’s support went beyond monetary means. His overarching dream was to promote tolerance by awakening an interest in these endeavors among the broader Christian population. While the Madonna points to the couple’s unquestioned allegiance to the Christian faith, their advocacy for a dialogue with the Jewish population certainly spoke to Schadow’s own preoccupation with his Jewish roots and the theme of conversion.

Cat. 10 Figures

Cat. 10a Wilhelm Schadow, Study of a Toddler’s Left Leg (for the figure of the Christ child), pencil heightened with white chalk, 15.5 x 16.5 cm, Künstlerverein Malkasten, Düsseldorf

Cat. 10b Wilhelm Schadow, Study of a Toddler’s Left Arm (for the figure of the Christ child), pencil heightened with white chalk, 14 x 18 cm, Künstlerverein Malkasten, Düsseldorf