Provenance

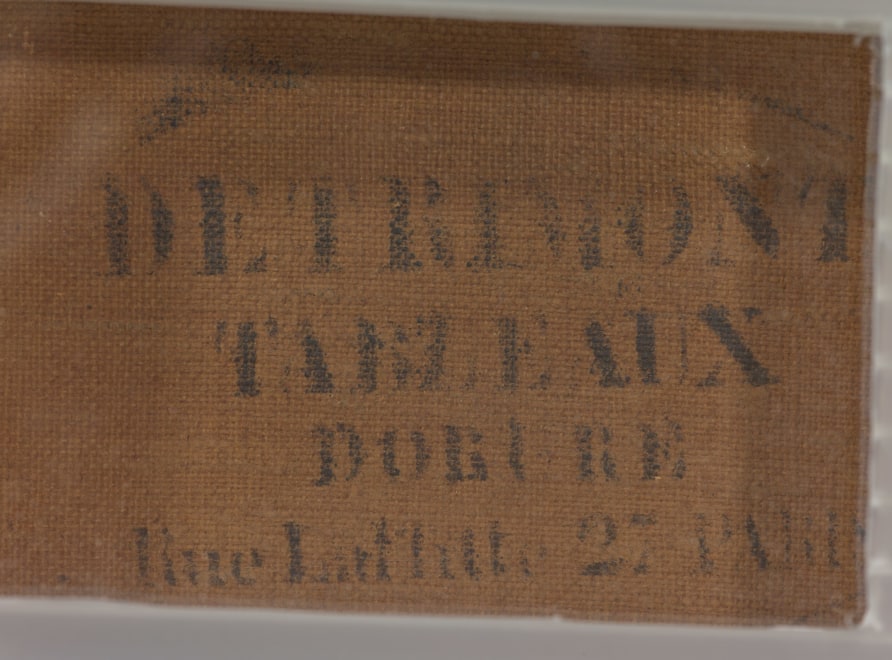

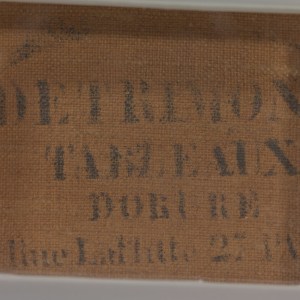

Artist’s studio (his sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 26 May-9 June 1875, lot 264)

Comte Armand Doria, Château d’Orrouy (Oise) (his sale: Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, 4-5 May 1899, lot 115)

F., Paris

Sale: Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 27 March 1953, lot 115

Sale: Sotheby’s, New York, 28 January 2010, lot 224

Private collection, USA (acquired at the above sale)

Exhibited

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, long term loan, 2013-2024

Literature

A. Robaut, L’Œuvre de Corot, Catalogue raisonné et illustré, Paris, 1905, vol. II, p. 50, no. 136, ill. vol IV, p. 225

A. Jullien, R. Jullien, “Les Campagnes de Corot au Nord de Rome,” Gazette des beaux-arts, XCIX, no. 1360/1361, May-June 1892, p. 189-190, note 37

Corot, 1796-1875, exh. cat., Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1996, p. 113. note 5 (under no. 23) (English version, p. 69, note 4)

Catalogue note

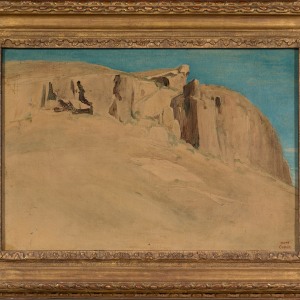

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a towering figure in the evolution of 19th-century art, forever changed the history of landscape painting. His work marks the moment when nature was no longer just a backdrop for human activity but a subject in its own right, deserving of close observation and deep emotional engagement. Corot’s innovative approach to light, atmosphere, and texture revolutionized the way artists perceived and represented the natural world. His mastery of capturing the fleeting effects of light, whether the soft glow of dawn or the dusky hues of evening, breathed life into his scenes, offering a sense of immediacy that had previously eluded the tradition-bound studio painters. For Corot, plein-air painting was not just a technique but a philosophy, as he sought to capture the soul of the landscape in its passing moments, turning each study into a meditation on nature’s beauty and transience.

Corot’s connection to nature deepened during his time in Italy, where the rugged landscapes and ancient ruins, which seemed to whisper tales of past civilizations, helped him further develop his plein-air technique.[1] Italy’s striking vistas, rich with both natural beauty and historical significance, challenged him to explore the interplay between nature and human history. It was here that Corot’s perception of the land transformed; Italy was not only a site of classical education but a place where nature and history intertwined, shaping Corot’s view of the landscape, with the southern sun illuminating his evolving understanding of light and form.

Corot embarked on his first journey through Italy in the spring of 1826, leaving behind his intense studies of ancient monuments in Rome. Accompanied by the German painter Johann Karl Baehr (1801-1869), he ventured into the heart of the Sabine Mountains, settling in the small town of Civita Castellana, just north of Rome.[2] A place rich with layers of history—once an Etruscan city, later a fortified medieval stronghold for the papacy, and now a wild and untamed landscape—the town provided an ideal setting for Corot’s studies of nature.[3] Its vegetation, trees, and rocks, perched on a plateau overlooking the scenic gorges carved by the Treja River, provided an ideal setting for the kind of studies Corot valued deeply, becoming a significant site for his artistic development.

During his visits, first in 1826 and again in 1827 with the painter Léon Fleury (c. 1804-1858), Corot produced a series of plein-air sketches and oil studies that captured the raw beauty of this ancient landscape. Approximately thirty oil studies, accounting for a quarter of his output during his entire stay in Italy between 1825 and 1828[4], were created here, many of which are now held in museums and private collections (Landscape at Civita Castellana, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; Landscape at Civita Castellana, Morgan Library & Museum, New York City; Civita Castellana, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Rocky Forest Valley at Civita Castellana, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Germany; Civita Castellana, Rochers rouges, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm).

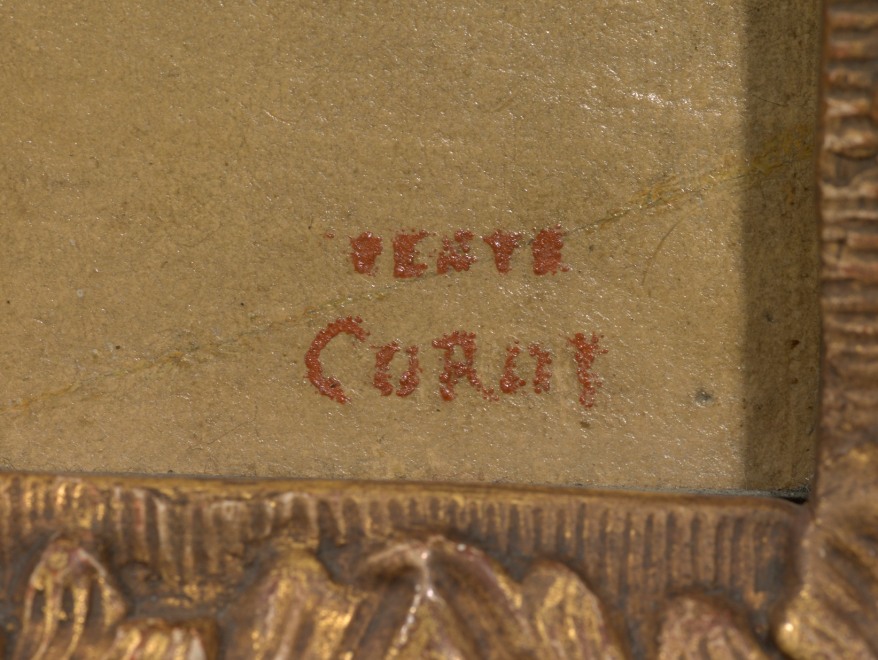

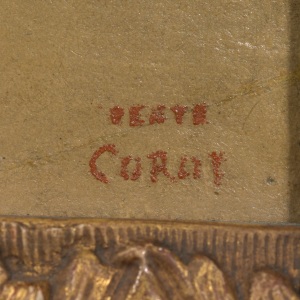

One of these paintings, Civita Castellana, High Rocks, stands as a cornerstone of Corot’s Italian series, capturing the stark beauty of the town’s eastern cliffs, composed of ocher-colored tufa stone.[5] The viewpoint Corot selected for this work, likely from near the Albergo di Tre Re, the inn where he and his painting companions stayed, offered a sweeping view of the surrounding landscape, including the three-arched bridge that once spanned the Treja River. The words of the French writer Chateaubriand (1768-1848)—“There is nothing comparable in beauty to the lines of the Roman horizon, to the gentle slope of its planes, to the soft, receding contours of the mountains by which it is bound[6]”—seem to echo the very inspiration Corot found in this dramatic landscape.

Corot’s careful handling of light and shadow emphasizes the rough terrain, with the cliffs rising in bold relief against the soft, diffused light of the Italian sky. The textured surface of the rocks, lit by the sun, brings out the contours of the mountains, magnifying their grandeur and evoking the timeless beauty that the artist sought to immortalize. In this landscape, light becomes a force that shapes the land, giving it depth and life, while the boldness of the forms imbues the scene with a sense of permanence and power.

This note was written by Elsa Dikkes.

[1] For Corot’s early periods in Italy, see Peter Galassi, Corot in Italy: Open-Air Painting and the Classical-Landscape Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991); and Gary Tinterow, Michael Pantazzi, and Vincent Pomarède, Corot (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996), pp. 5-84.

[2] Gary Tinterow, Michael Pantazzi, and Vincent Pomarède, Corot (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996), p. 68.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] André Julien and Renée Julien, “Les Campagnes de Corot au nord de Rome,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts XCIX, nos. 1360/1361, May-June 1982, pp. 189-90, 199, note 37.

[6] Quoted in Galassi, Corot in Italy, p. 15.