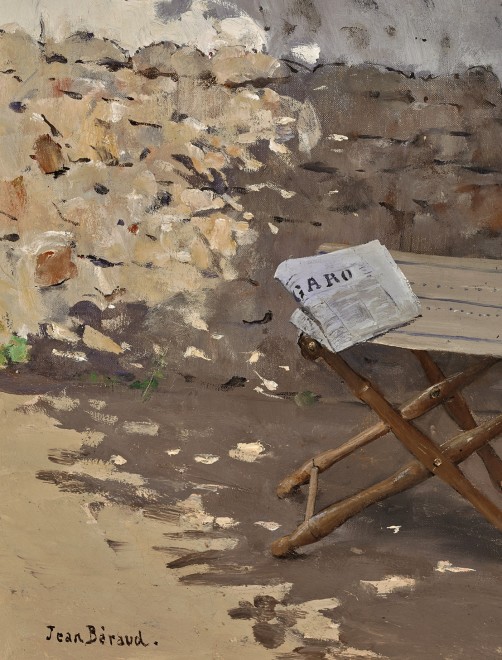

64.8 by 54.6 cm.

Known for his impressionistic depictions of urban Parisian life, Béraud offers a rare respite from the bustling metropolis in Un Figaro de rêve.

Provenance

G. von BodemM. Morel

Galerie Brame et Lorenceau, Paris (1986)

Noortman Gallery, Maastricht

Private Collection, Connecticut (acquired from the above in 1999)

Exhibited

Paris, Grand Palais, XIIIe Biennale internationale des antiquaires, 1986, illustrated p. 7 (Brame et Lorenceau)Maastricht, The European Fine Art Fair, 1999 (Noortman Gallery)

Literature

S. Haitay, “Un événement. La XIIIe Biennale des antiquaries,” Le Figaro, September 20, 1986, p. 196, illustrated (black and white)Patrick Offenstadt, Jean Béraud 1849-1935, The Belle Époque, A Dream of Times Gone By, Catalogue Raisonné, Köln, 1999, illustrated p. 235, no. 305 (color)

The Magazine Antiques, vol. 164, issue 1, July 2003, illustrated inside front cover (color)

Catalogue note

Jean Béraud is above all a collector of human documents and a searcher after picturesque subjects [. . . ] [He is a] modern master [. . . ] who paints neither the old that exists no longer nor the future which does not yet exist, but only the reality of today, and who sees life only in the present hour and the moment now passing – who seizes it – M. Jean Béraud gives to his least works an intensity of life and a surprising reality (trans. from the original French, Louis Énault, “Jean Béraud: La Salle des Filles au Dépôt,” Paris-Salon 1886, vol. 1, 1886, pp. 11-12).

Known for his impressionistic depictions of urban Parisian life, Béraud offers a rare respite from the bustling metropolis in Un Figaro de rêve. The figure of a fashionably dressed woman, seen from the back but twisted slightly to echo the curve of the river behind her, recalls another work by the artist, La Boule de Verre of 1875 (private collection).[1] It is likely that the present painting dates to approximately the same early period, when the influence of Impressionism on Béraud was at its greatest. (Just one year earlier, in 1874, the first of eight exhibitions of Impressionist painting was held in Nadar’s studio in Paris, featuring works by Camille Pissarro [1830–1903], Alfred Sisley [1839–1899], Edgar Degas [1834–1917], Claude Monet [1840–1926], Berthe Morisot [1841–1895], and Pierre-Auguste Renoir [1841–1919]. Maligned by critics, one of whom coined the term impressionisme pejoratively after Monet’s Impression: Sunrise, 1872 [Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris], this group of artists dedicated themselves to the depiction of modern life, especially landscape and genre subjects, based on direct observations en plein air. They developed a style of painting with loose, broken brushstrokes that mirrored the fleeting nature of their subjects and the vibrant, almost palpable energy of the nineteenth-century Parisian world.) A close friend of Manet (1832-1883), Béraud also looked to Degas as a mentor, and frequented the same cafés, restaurants, and theaters as Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and other leading artists of the day. The result of these relationships is clearly witnessed in Béraud’s art, as elements of their distinctive styles were translated, reinterpreted, and selectively incorporated into compositions such as this one.

The sense of time and its passage that the flick of Béraud’s brush creates in this particular work is compounded by the inclusion of a newspaper – the choice of Le Figaro in particular, issued daily after 1866, marks the moment as both topical and temporal, and as fleeting as the play of light across varied surfaces, which Béraud has tried to capture here.[2] Such attention to the temporary nature of the world in which he lived is witnessed in others of Béraud’s canvases, such as his Les Grands Boulevards (Café Américain) (private collection) of ca. 1897, in which posters clearly advertise a variety of upcoming events. In 1889, moreover, Béraud was commissioned to paint La salle de rédaction du Journal des débats (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) – a rare subject in his oeuvre, but in keeping with the scientific and business interests compelled by such influential artistic movements as Naturalism and Positivism, of which Béraud was tangentially a part.

Set in the suburbs, a new and important theme in nineteenth-century art and literature, particularly among the Impressionists and Realist artists such as Jean-François Raffäelli (1850-1924) (see the Gallery 19c inventory for an important example of this artist’s banlieue themes), the subject of this work might be compared to the isolated female figures that populate many of Béraud’s metropolitan scenes.[3] Rather than shopping along Paris’s boulevards or navigating a busy public square, however, this woman is cast as a thoughtful reader of current events. With no need for a chaperone, and clearly at ease in her pastoral location, she cannot be mistaken for a powerless or decorative object. Le Figaro rests precariously on the folding seat by her side, abandoned for the moment as the woman contemplates what she has read. (The trope of reading was a common one in nineteenth-century art, and in particular in the works of the Impressionists. Typically, however, it was the act of escapism and quietude that was their focus, rather than the political, historical, or literary content of the texts themselves. In time, works of art featuring newspapers evolved to become purveyors of specific political commentary, and a subject in and of itself. Beginning in the early 1900s, Georges Braque [1882-1963] and Pablo Picasso [1881-1973] – both loyal readers – started the art of collage, cutting bits of newspapers and pasting them on canvas.) It is hard not to imagine that Béraud’s tendency to create images glossed with humor or even mockery of contemporary Parisian culture may be at play in this rare work. The painter associated so closely with the superficialities and glitter of modern urban life here seems to mimic his subject, seeking meditative respite in the city’s suburbs - albeit, given the lure of Le Figaro’s printed words, not as successfully as he might hope.

This note was written by Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D.

[1] This posture is also reminiscent of the figurative paintings of Childe Hassam (1859-1935), whose depictions of fashionably clad women from the back form a distinct subgroup within his oeuvre.

[2] The first daily edition of Le Figaro, issued on November 16, 1866, sold 56,000 copies; this was the highest circulation of any newspaper in France.

It is interesting given this interest in the momentary and the fleeting, that Béraud’s attention to fashion is not more specific; the dress of the woman in the present work is of the moment, to be sure, but it is not rendered with the specificity that a clothing historian might expect.

[3] A series of eleven works by Béraud, for example, feature a single female figure in the Place de la Concorde.