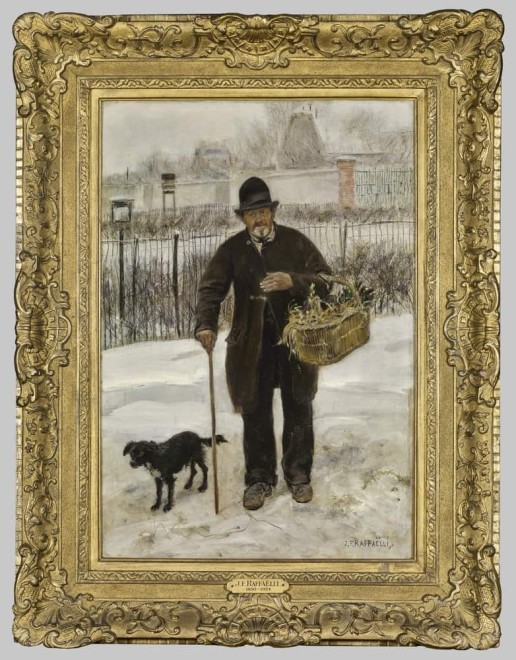

54.6 by 37.4 cm.

“When one paints the people,” declared Raffäelli, “one must never have pity on their state,...nor should one flatter them or paint them as sublime, as have done certain unphilosophic painters. One should paint them in their place, with kindness and sympathy, while keeping one’s distance,... It is the best way of showing them,..."

Provenance

Sale: Hôtel des ventes d’Evreux, Evreux, France, December 1, 2016, lot 47Catalogue note

In studying [Raffäelli’s] work astonishment is felt at his variety, his dramatic instinct, his power to catch not only the character of the people in the streets but their movement. He seizes the transient with the accuracy of the camera, but at the same time he gives what no camera ever detects, for he looks into the souls of the people passing and records the struggle, the hope, the despair, the loneliness of their lives (“Jean François Raffäelli,” The Art Interchange, vol. 34, no. 4, April 1, 1895, p. 111).

In 1888, Raffäelli embarked on his most ambitious and arguably his most important artistic venture, Les Types de Paris (Paris, 1889).[1] In this series of short stories written by a variety of authors (comprised of the leading Naturalist and Realist writers in Paris at the time) and extensively illustrated by Raffäelli, one chapter stands apart.[2] Undertaken with his good friend Mallarmé (1842-1898), “Types de la Rue” featured pictures and poems documenting figures drawn from French urban and suburban life, and in particular the hardworking and often downtrodden street merchants and vendors of various goods.[3] The present work is a reinterpretation of one of the most poignant of these figures, Le Marchand d’ail et d’oignons, and stands as a powerful example of Raffäelli’s revolutionary caractériste style.[4]

Called the “peintre de la banlieue” for his commitment to the depiction of Paris’s blighted suburban scene,[5] Raffäelli moved in 1878-9 to Asnières, a popular Parisian resort (and burgeoning industrial) town on the Seine.[6] Here, and in the areas near Clichy and Levallois-Perret, he was able to articulate and develop his artistic theory, called caractérisme, which went beyond a literal description of nature to reveal the essential – and, for Raffäelli, beautiful - character of even the bleakest aspects of contemporary society and its individuals.[7] “Thanks to M. Raffäelli,” wrote the French critic Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), “the banlieue of Paris – this intermediary and bizarre world, at once swarming and abandoned, no longer the city and not yet the country, where nothing ends, and where nothing begins, where men, poverty-stricken wrecks: small bourgeois lives, strange trades, nocturnal prowls, proletarian defeats; where skies loaded down with the soot of factory chimneys, the acrid odor of urban dust, where landscapes, made of etiolated vegetation, of gray profiles, of dreary silhouettes, of smoky horizons, of detritus, stones, and plaster, relieved, here and there, by a vivid fragment of broken tile or the glitter of a shard of glass, all have such a particular character of suffering and of revolt, such a poignant color of melancholy – has won its place in the ideal.”[8]

Raffäelli’s philosophy found its most vivid expression in his portraits of peasants and street merchants, who were portrayed with a combination of objectivity, compassion, and penetrating insight.[9] “When one paints the people,” declared Raffäelli, “one must never have pity on their state, under penalty, if one appeals to pity, of degrading them and degrading oneself: nor should one flatter them or paint them as sublime, as have done certain unphilosophic painters. One should paint them in their place, with kindness and sympathy, while keeping one’s distance, and with a profound aristocratic sense. It is the best way of showing them, whatever one may think of it, our brotherly feeling, and of raising them to our level, without risk for them or for us.”[10] This skillful navigation between the elevation of character and emotional restraint (maudlin sentiments have no place in Raffäelli’s art) resonated with contemporaries, who saw in his subjects the echo of Millet (1814-1875). “[A]mong the mass of exhibitors in our time,” wrote an ardent supporter, “M. Raffäelli is one of the rare who will remain; he will stand out from the art of the century, as a kind of Parisian Millet, influenced by certain melancholies of humanity and of enduringly rebellious nature.”[11] Albert Wolff (1835-1891), who wrote one of the most widely read and influential reviews of Raffäelli’s work in Le Figaro in 1881, and who himself owned several of Raffäelli’s paintings, including a much-admired version of Le Marchand d’ail et d’oignons (now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), concurred: “. . . like Millet he is the poet of the humble. What the great master did for the fields, Raffäelli begins to do for the modest people of Paris. He shows them as they are, more often than not, stupefied by life’s hardships.”[12]

In Promeneur et son Chien, the hardships are subtle but clear. The merchant, an allium seller, pauses for a moment with his walking stick, as he traverses the bleak and snowy landscape of the banlieue.[13] The pronounced verticality of the stick echoes the lines of the fence behind him, calling attention to the inhospitality of this divided ground.[14] (The subdued palette, thinly applied paint, and linear, graphic style of these elements of Raffäelli’s picture reflect the qualities that he had developed as a self-trained illustrator and printmaker during the course of his long and varied career.[15]) The man’s beard, whitened with age and toil, and the muted colors of his well-worn coat and suit – vestiges, perhaps, of an erstwhile bourgeois life – unite him with his four-legged companion, a scruffy black and white dog.[16] The dialogue that this visual bond creates is problematized by the comportment of the pair; rather than engaging in any physical connection, the two stand awkwardly apart.[17] Independent and self-reliant, Raffäelli seems to suggest these inhabitants of the banlieue are also distant and alone.

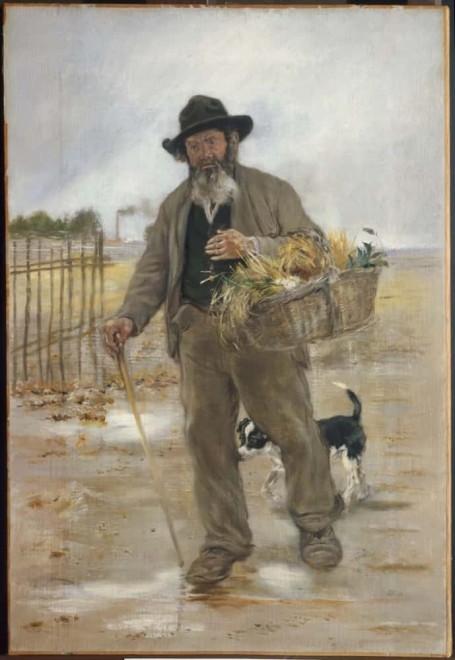

Two versions of this painting are known:

Jean-François Raffäelli, Garlic Seller, 1881, oil on paper mounted and extended on canvas, 28 ¼ x 19 ¼ in. (72 x 49 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Henry C. and Martha B. Angell Collection, 19.103

Jean-François Raffäelli, Le Marchand d’ail et d’oignons, engraving, from “Types de la Rue,” Stéphen Mallarmé, Les Types de Paris, Paris, 1889, n.p.

This note was written by Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D.

[1] Les Types de Paris appeared in ten weekly installments from February 1, 1889, and was published by Plon. Nourrit & Cie. for Le Figaro.

[2] Among the twenty other writers for this project were Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), Émile Zola (1840-1902), J. K. Huysmans (1848-1907), and Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893).

[3] The collaborative effort between Raffäelli and Mallarmé resulted in the seventh installment in the series (see note 1). Their extensive communications during the course of the project are housed, in part, in the Mallarmé archive at Valvins.

[4] Raffäelli produced a number of drawings and prints related to his paintings – and vice versa - including Le Marchand d’ail et d’oignons. One of these, The Garlic Seller of 1881 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), was owned by the critic Albert Wolff (1835-1891) (see text of note above). Wolff would later write the introduction to Les Types de Paris.

[5] The art critic Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) went so far as to declare in 1886 that Raffäelli had “invented the suburban landscape,” (Félix Fénéon, “Le Musée du Luxembourg,” Le Symboliste, October 15, 1886, reprinted in Oeuvres plus que complètes, ed. Joan U. Halperin, Geneva, 1970, p. 63.

[6] Popular with artists, the town was famously portrayed by van Gogh and in Seurat’s Bathers of 1883-4, (National Gallery, London). Of one of his pictures of Asnières, Seurat wrote, “I am doing a Raffäelli, apparently,” (Georges Seurat to Paul Signac, June 16, 1886, quoted in T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, 1984, 2nd ed., Princeton, 1999, p. 273, note 5).

[7] As Raffäelli declared, ““[T]here is no beauty in Nature; beauty resides in character,” (quoted in Gabriel Mourey, “The Work of Jean-François Raffäelli,” The Studio, vol. 23, no. 99, June, 1901, p. 8). See also Jean-François Raffäelli, trans. Isabel McDougall, “Realist and Idealist,” The Art Interchange, vol. 36, no. 1, January 1, 1896, p. 2. The association of Raffäelli’s suburban scenes with beauty was articulated by contemporaries, as well, including Auguste Rodin (1840-1917): “Raffäelli is an artist for whom the word original was coined. Without him, we would pass through the banlieues without knowing the beauties that lay within,” (Auguste Rodin, quoted in “Jean-François Raffäelli, 1850-1924,” Gustave Geffroy, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 5, no. 10, 1924, p. 173).

[8] “Jean-François Raffäelli,” L’Écho de Paris, May 28, 1889, reprinted in Octave Mirbeau, Combats esthétiques, 1877-1892, ed. Pierre Michel and Jean-François Nivet, vol. 1, Paris, 1993, p. 367.

[9] Raffäelli’s unique point of view may have owed something to personal experience: after repeatedly advising artists to paint only the things they knew (“I feel that no artist should paint what he does not thoroughly understand,” [Catalogue of works of Jean François Raffäelli. Paintings, drypoints and etchings printed in color, exh. cat., Art Institute of Chicago, 1900, p. 11)]), he attempted to explain the empathy he felt for his subject matter: “My life has not been an easy one, for I was brought up in luxury until I was fifteen, when within a few years my family lost its entire fortune and I became acquainted with the most grinding poverty. Then came the war . . . At that period I painted with the greatest sincerity my hopelessness, my bitterness, my anger, my madness. It follows then that my art was a violent art, somber, bitter, hopeless. I was at that time consumed with the greatest pity and commiseration for those who had been defeated in the great battle of life,” (ibid., p. 12). Despite these sentiments, Raffäelli warned against conflating an artist with his work: “If you paint workers, you are a communard-anarchist-socialist-realist-revolutionary . . . and déclassés, you are one yourself,” (Jean-François Raffäelli, Catalogue illustré des oeuvres de Jean-François Raffäelli, exposées 28 bis, avenue de l’Opèra, suivi d’une Étude des mouvements de l’art modern et du beau caractériste, Paris, 1884, p. 38).

[10] Letter to Arsène Alexandre of 1909; reprinted in J. Isaacson, The Crisis of Impressionism, 1878-1882, Ann Arbor, 1980, p. 166.

[11] J. K. Huysmans, “L’exposition des indépendants en 1881,” in L’art modern/Certains, Paris, 1975, p. 220. Some years later, Huysmans would repeat these sentiments, in equally eloquent terms: “[Raffäelli] is the Millet of Paris, and he is alive to the melancholy of humanity as well as to all the poetry of Nature and all the moods of the various struggles of city and country,” (quoted in “Raffäelli, A French Painter of the People,” Delia Austrian, The Craftsman, vol. 22, no. 3, June 1, 1912, p. 253).

Jean-François Millet was one of the founders of the Barbizon school in France; he is best known for his heroic images of peasant farmers.

[12] Albert Wolff, “Courrier de Paris,” Le Figaro, April 10, 1881, p. 1. In 1881, Wolff’s Garlic Seller was displayed at the sixth Impressionist exhibition, where it drew crowds of admiring viewers (“Beaux-Arts: Sixième exposition des artistes ‘independants,’” Le Petit Parisien, April 8, 1881, p. 3).

[13] Raffäelli’s study of the banlieue included all four seasons; several of his prints and paintings feature a snow-covered landscape.

[14] Often in Raffäelli’s works, and as several contemporaries noted, the landscape acts as a reflection or commentary on the physiognomy, condition, or mood of his human subjects: “At first M. Raffäelli saw and depicted this special section of humanity in the most tragic light, and his wild, lonely backgrounds were in full harmony with the moral and material misery of his figures,” (Mourey, p. 13).

[15] Raffäelli was, in addition to a painter, an accomplished printmaker, draughtsman, sculptor, and author.

[16] Between 1879 and 1884, the ragpicker, or Chiffonnier, was the most consistent and prominent character in Raffäelli’s banlieue; these figures were sometimes portrayed wearing the cast-off clothes of the bourgeoisie, a poignant allusion to social aspirations and class strife.

The pairing of man and dog was a common trope in Raffäelli’s art: the titles of at least seven prints and paintings directly address this theme. For more on the dog in late nineteenth-century French art, as both accessory and symbol, see Richard Thomson, “ ‘Les Quat’ Pattes’: The Image of the Dog in late Nineteenth-Century French Art,” Art History, vol. 5, no. 3, September 1982, pp. 323-37.

[17] In Le Marchand d’ail et d’oignons, the situation is very different: here the dog appears to be intertwined with the legs of his friend and master, and thereby integrated into his form. The differences between this work and the Gallery 19c version are, in fact, many, and offer an intriguing glimpse into Raffäelli’s development of a composition and its meaning.