Provenance

Paul Rosenberg & Co., Paris & New York

Probably, Alex Reid & Lefevre, London

Margaret Thompson Biddle Schulz, USA

Thence by descent, Joyce Ward MacKenzie, New York, 1956

Thence by descent to the present owner

Exhibited

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Collects, Paintings, Watercolors and Sculpture from Private Collections, 1968, no. 204, p. 41

Literature

Lionello Venturi, De Manet à Lautrec, Paris, Alban Michel,1953, ill. p. 110

François Daulte, Alfred Sisley, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Lausanne, ed. Duand-Ruel, 1959, no. 11, ill., p. 45

François Daulte, Sisley, Milan, Fratelli Fabbri, 1974, ill. p. 74

Sylvie Brame & François Lorenceau, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue critique des peintures et des pastels, Lausanne & Paris, 2021, no. 12, ill., pp. 44, 408

Catalogue note

The pivotal Paris Salon of 1859 marked a shift in the evolution of French landscape painting. The long-established tradition of the classical landscape (paysage héroïque) was pretty much left behind in favor of a new naturalism and realism that combined elements found in both Corot and Rousseau, together with an unavoidable sprinkling of Courbet. This was the environment that greeted the next generation of landscape painters, those artists who would later become known as the Impressionists in the 1870s; we are speaking specifically of Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley.

There was a stylistic affinity in the landscapes produced by these artists in the 1860s, especially the latter years of the decade. After meeting as students at the studio of Charles-Gabriel Gleyre in the early 1860s, the newly formed group of friends, which also included Bazille and later Pissarro, headed to the Forest of Fontainebleau. Keenly aware of the previous generation of landscape painters, especially Corot, Rousseau, and Millet, it was natural that the young artists would be drawn to Barbizon, at the time the most important artist’s colony in France. But rather than emulate the philosophy of the earlier artists, they approached landscape differently. Gone was the sentimentality that often characterized the works of Corot and Rousseau, where often the artist became deeply and personally connected with the subject, as so aptly described in this well-known quote by Théodore Rousseau: “I heard the voices of the trees; the surprises of their movements. Their varieties of form and even their peculiarity of attraction toward the light had suddenly revealed to me the language of the forest…I wished to converse with them and to be able to say to myself, through that other language, painting that I had put my finger upon the secret of their grandeur.” (as quoted in Charles Sprague Smith, Barbizon days, Millet-Corot-Rousseau-Barye, New York, 1902, p. 147.) This type of anthropomorphism was far from the goal of the new painters, who preferred a more objective approach to depicting their subject. What mattered to them was not a direct and personal connection but rather an understanding of how light, color and texture ended up defining a landscape, whether it be a field, a rocky plateau, or a tree.

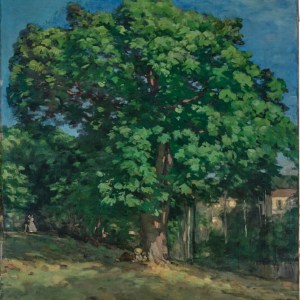

Painted in 1868, Sisley’s À la Lisière de la Forêt de Fontainebeau shows a large tree, its branches bursting with vibrant green leaves. Perhaps it is spring or early summer; a young man leans against the trunk of the tree, reading a book while the tiny figures of a couple can be seen embracing in the distance. Although three people populate the scene, the subject is all about the massive tree. The idea of painting a tree as the primary focus had precedent in two contemporary paintings: Gustave Courbet’s The Oak of Flagey of 1864 (Courbet Museum, Ornans) and Monet’s majestic The Bodmer Oak, painted in 1865 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). However, the young Sisley is more daring; his tree takes up the entire surface of the painting, in other words, he has painted a “close up”. The leaves are large and lush painted with overlapping dabs and splashes of various shades of vibrant green. Areas of sunlight reflect on the trunk and branches of the tree. This is a Sisley we have not seen before. His paintings from the 1860s are very rare. During the Franco-Prussian War, Sisley’s house in Bougival was occupied by the Prussian army, and most of his work from the 1860s was likely destroyed during the bombardment of the Paris suburbs that followed.