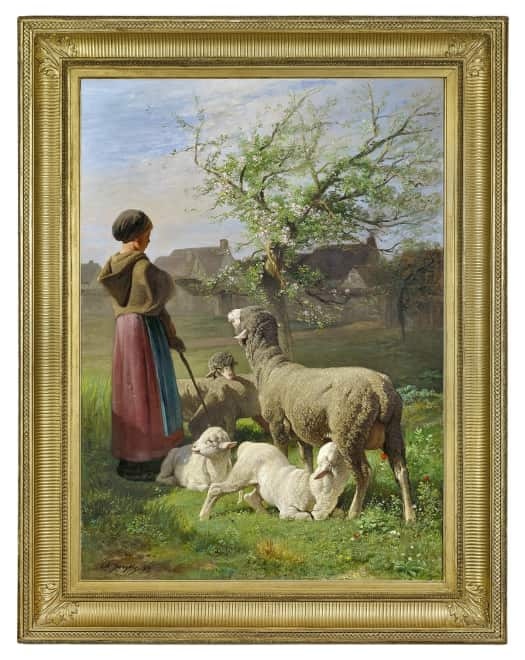

106.7 by 76.8 cm.

A testament to its popularity, perhaps, and the special place it held in Jacque’s own, expansive oeuvre, several, nearly identical versions of Le Printemps were produced on panel and canvas, and multiple prints, drawings, and preparatory works are known as well. It is likely that the Gallery 19c version – the only by the artist to be ascribed a date - is among the earliest of the group; a smaller picture now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, painted on wood and measuring 16 x 11 ½ in. (40.6 x 29.2 cm), reverses the composition, perhaps due to Jacque’s intent to later engrave the work.

Provenance

Possibly, M. Zygomalas, Marseilles, before May 1900 (Goupil stock book 14, stock no. 26681, p. 250, row 13)Possibly, Charles A. Gould, New York, after November 1900 (Goupil stock book 14, stock no. 26681, p. 250, row 13)

Private Collection, Buenos Aires

Sale: Sotheby’s, New York, April 23, 2004, lot 3

Exhibited

Buenos Aires, Galerias Witcomb, Exposition of 19th Century Painting, June 2–21, 1947, no. 63Literature

Katherine Baetjer, European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1995, p. 419 (as Springtime)Catalogue note

In 1844, at the age of 32, the accomplished engraver and etcher Charles Émile Jacque (1813-1894) took up painting. Within ten years, he had made his name as both a founding member of the “School of 1830,” or Barbizon School, and one of France’s leading Realists and animaliers. Jacque’s particular affinity for bucolic depictions of sheep and shepherds – subjects he repeated numerous times during the course of his long and prolific career - earned him the sobriquets the “prince of sheep painters” and the “Raphael of sheep,” and the admiration of collectors across the globe.[1] The present work, painted in 1859, features one of the artist’s favorite variations on this theme, and demonstrates both Jacque’s unparalleled knowledge of his subject matter and his ability to seamlessly combine the grand scale, profound messaging, and self-importance of a Salon-type painting with the humbleness, introspection, and tranquility of the French countryside.

The year that Le Printemps was painted was a meaningful one for Jacque, with the birth of his son Fréderic (1859-1931) and a series of professional successes and milestones.[2] After several profitable sales and well-received exhibitions of his engravings,[3] including the debut of his most famous sheep picture, the massive La Grande Bergerie,[4] Jacque’s confidence in his work was high. The dimensions of his paintings began to increase accordingly, as they pronounced themselves to be “Salon-worthy,”[5] and their perspectives began to (literally) shift and change; objectivity and scientific detachment gave way to the perfection of an artistic device that would become the signature of Jacque’s mature style - the low vantage point, or intimate and empathetic “sheep’s-eye view.” The artist’s capacity to identify with his animal subjects, as well as to accurately record their appearances and actions, may be traced to his arrival with Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) at the picturesque town of Barbizon in 1849, and his ensuing interest in nature and local farming practices.[6] Not content to merely observe the life around him, or romanticize its ways, Jacque took it upon himself to develop real estate in the region, cultivate asparagus, breed poultry, sell eggs as part of an entrepreneurial business venture, pen scientific and technical articles regarding all aspects of agriculture, and write a definitive guide to chickens, entitled Le Poulailler, in1858.[7] Jacque also befriended a small flock of tame sheep, the members of which served as his most instructive and devoted models as he painted en plein air.[8]

The works that Jacque produced during and after this profoundly influential period - among the most popular of his day - have recently experienced a resurgence of interest among scholars and collectors, both for the art historical traditions they preserve and the remarkable originality of their vision. In their compositions is found the deliberate invocation of an earlier age, not merely in terms of subject and technique,[9] but in the artist’s repeated attention to a rural agricultural economy governed by seasonal cycles, weather, and times of day. The title of the present work is a clear reminder of this tendency. (The theme of “spring,” in fact, occurs repeatedly in Jacque’s oeuvre, while other works depict the countryside in summer, winter, and fall.[10] An album of wood engravings [Album de sujets rustiques], also published in 1859, depicts the entire course of agricultural seasons, month by month, in the fashion of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry [1412-16] and other medieval Books of Hours.)[11]

Jacque’s historical references could be far more topical as well. The artist’s constant reiteration of images of flocks of sheep grazing in a rocky field, for example, was not a sight he would have witnessed during his years in Barbizon, but rather a nostalgic memory of open pasture grazing, a practice that had ended in the area almost completely by the mid-1800s.[12] The motif of the nursing lamb in Le Printemps could, by 1859, be called into question as well: with the rise of industry and market demand, lambs were weaned earlier and earlier during the second half of the nineteenth century, making Jacque’s sizeable youngster the exception to contemporary farming methods, rather than the rule. Jacque’s ability to create a sense of authenticity by simply repeating a scene until familiarity rendered it true, is but one of the qualities that sets his artistic process, and his richly complex images, apart from those of his peers.

More significant, however, is the figure of the shepherdess herself. Pensive, anonymous, and connected to the earth by virtue of her staff, her stoic silhouette recalls the laborers of other Barbizon and Realist painters, and in particular Millet. This comparison – one that can be made repeatedly throughout Jacque’s expansive oeuvre - has led many scholars to ascribe the influence of this master on his friend and colleague Jacque. Careful research, however, reveals that the opposite was true: it was Jacque who first adopted these subjects as his theme, and heroic rusticity – in animals as well as in people - as his aesthetic and philosophy.[13]

The appeal of Barbizon subjects among nineteenth-century artists and collectors occurred at a time when the need for escape – both real and imaginary – was high. As regional tourism grew exponentially, and parks and outdoor spaces were constructed in nearly every city and town, France’s urban population began to view Barbizon paintings as another kind of sanctuary in the chaos of modern life.[14] Exhausted by industry and concerned about its affect on the countryside, Jacque’s paintings of bucolic landscapes, honest, simple work, and cows, chickens, and especially sheep, with their vaguely religious overtones,[15] met a need amongst disillusioned mid-century audiences that other genres simply could not fill. The epic proportions of his pictures, moreover, assured collectors of their worth; if seemingly mundane in subject, they were clearly no less worthy of respect and high repute.

A testament to its popularity, perhaps, and the special place it held in Jacque’s own, expansive oeuvre, several, nearly identical versions of Le Printemps were produced on panel and canvas, and multiple prints, drawings, and preparatory works are known as well.[16] (The theme of a shepherdess or shepherd and their flock was itself a favorite of Jacque’s and reappears in part or in whole in scores of works throughout his mature career.)[17] It is likely that the Gallery 19c version – the only by the artist to be ascribed a date - is among the earliest of the group;[18] a smaller picture now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, painted on wood and measuring 16 x 11 ½ in. (40.6 x 29.2 cm), reverses the composition, perhaps due to Jacque’s intent to later engrave the work. A third version (present location unknown), once owned by “M. Zygomalas de Marseille,” is the largest of the paintings, measuring 84 x 60 in. (213.4 x 152.4 cm). Zygomalas, a French merchant and prolific art collector active at the turn of the twentieth century, may have owned as many as three versions of Le Printemps, including the present work, at the same or various times.[19]

The appearance of Jacque’s work in a private collection in Buenos Aires and at an exhibition in that same city in 1947 is indicative of a larger phenomenon. In the late 1880s, on the heels of an unprecedented financial boom, Buenos Aires experienced an unparalleled influx of European paintings and sculpture and the meteoric rise of a new breed of Argentinian collectors. Eager to compensate for the lack of art institutions in their native country, these men and women regularly shared their works with the public at large, through loans, the opening of their private residences to public view, and the founding of exhibition spaces and galleries, including the Galerias Witcomb. Barbizon paintings featured strongly in these new collections, with Jacque a ubiquitous favorite.[20]

This note was written by Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D.

[1] Indeed, by 1895 one contemporary writer could proclaim that, “‘No collection of the Barbizon school is complete without a specimen from the hand of Jacque,” (W. A. Cooper, “Private Picture Galleries in the United States III,” Godey’s Magazine [January 1895], p. 3).

Despite the preponderance of sheep pictures in his expansive oeuvre, some might argue that chickens were Jacque’s true love. According to one critic, Jacque painted chickens “for his own pleasure while he painted sheep to please his patrons,” (“The Collector,” Art Amateur: A Monthly Journal Devoted to Art in the Household 401 [December 1898], p. 4). The critic went on, “Visitors to his [Paris] studio in the Boulevard de Vichy would usually see, conspicuously exhibited on an easel, a big picture of sheep under a group of oaks in the brownish red of their autumnal foliage, with glimpses of blue sky and gray clouds through the branches. But if the visitor showed that he appreciated this somewhat somber color harmony, Jacque would quickly place before him some three or four of his poultry pictures, over which he would gloat as an old trout-fisher does over the ‘speckled beauties’ and ‘red hackles’ and ‘silver grays’ among his favorite flies,” (ibid.)

[2] Along with Jacque’s son Emile (1848-1912), Fredéric would become a painter and engraver of rural subjects.

[3] In this year, Jacque exhibited his works at Saint-Etienne and Marseilles, among other locales. In 1860, he would exhibit four works on the Boulevard des Italiens in Paris, along with several other Barbizon artists.

[4] A painted version of this work, dated 1881, is currently at the Musée d’Orsay.

[5] The monumental scale of many of Jacque’s paintings - and even his engravings, etchings, and other printed works - is indicative of the artist’s conviction that rural subjects were worthy of the same treatment as history painting, and of his quiet but revolutionary effort to overturn traditional hierarchies within academic art.

[6] In 1849, fleeing a devastating cholera epidemic in Paris, Jacque traveled with his family to the scenic French town of Barbizon with his friend and fellow artist Millet. Though Jacque was spending more time in Paris than in Barbizon by the mid-1850s, the majority of his mature works continued to focus on scenes of rural farm life, as Le Printemps attests.

[7] Jacque’s broad interests continued throughout his life, extending to manufactured goods and handicrafts as well: In the 1870s, he became involved with the production and radical redesign of Renaissance and Gothic furniture at a factory in Le Croisic.

[8] Hoeber, pp. 282-3. One of Jacque’s paintings may humorously reference this anecdote: Jacque depicts one of his ubiquitous sheepfolds with an artist’s easel and painting (Sale: Weschler’s Auctioneers, Maryland, November 16, 2012, lot 290).

[9] Jacques is often credited with single-handedly reviving and reinventing the art of etching in France.

[10] The Brooklyn Museum, for example, has Jacque’s etching of Winter, ca. 1865, in its collection, and the prominent collector George Seney (1826-1893) owned Jacque’s painting Summer of 1866.

[11] A befitting inspiration for a Barbizon artist, these medieval manuscripts were instrumental in the development of landscape painting, as their illustrations were among the first to give prominence to this subject.

[12] Though unrealistic, these references may be considered valuable acts of “salvage ethnography,” useful to historians of French agricultural practices in the Barbizon region.

[13] In recognition of this fact, one contemporary writer made the following recommendation: “To Jacque, therefore, might well be accorded some of the excess of lustre shed upon Millet in his rôle of innovator,” (Frank L. Emanuel, “The Etchings of Charles Jacque,” The Studio 34 [1905], p. 218). For additional contemporary discussions of the artistic relationship between Millet and Jacque, see René Ménard, “Charles Jacque,” The Portfolio 6 [January 1875], pp. 130-1; Hoeber, pp. 28, 276-7; and Loys Delteil, The Print Connoisseur 2.4 (June 1922), p. 314. For Jacque’s critical role in the development of Realism in French art, see Gabriel Weisberg, “Charles Jacque and Rustic Life,” Arts Magazine 56.4 (December 1981), pp. 91-4.

[14] Contemporaries’ search for “silence and solitude” through nineteenth-century imagery will be explored in depth in a forthcoming exhibition at Gallery 19c.

[15] Due to his period of residency in London, and his close ties to the British art world later in his career, Jacque may have known the work of the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), and his unique brand of typological symbolism. Of particular interest in the context of Le Printemps is Hunt’s Our English Coasts of 1852 (Tate Britain), a work featuring “strayed sheep” painted en plein air, and rich in political and religious significance.

[16] The similarity of titles among Jacque’s works – often identical and always vague – as well as the repetition of subject matter and even dimensions has made the determination of individual picture’s provenance and exhibition histories challenging at best. The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, for example, in its account of the collection of late Professor Peck of Rochester, describes a painting that could be any number of Jacque’s works, including a version of Le Printemps: “Among the most important paintings in the collection, which numbers nearly one hundred, may be noted a superb example of Charles Émile Jacque, the world renowned sheep painter of Paris, the canvas measuring about 30 x 40 inches, representing a flock of sheep attended by a shepherd, grazing in a picturesque landscape. This picture is well known as one of the best of the artist’s works . . .,” (March 28, 1894, p. 10). A lithograph, moreover, also titled Le Printemps, is recorded in Verzeichniss der Kupferstich-Sammlung in der Kunsthalle zu Hamburg (Hamburg, 1878), and is listed as no. 179 in L’Oeuvre de Ch. Jacque: Catalogue de ses Eaux-Fortes et Pointes Sèches by J. -J. Guiffrey (Paris, 1866). The brief description here is the only indication that the subject is in fact different than that of the present work. Finally, there has been much confusion in the art historical literature regarding the popularity of the Gallery 19c version of Le Printemps in the popular press: it is similar to, but not the same work as, a work reproduced in Le Magasin Pittoresque of 1860.

Of preparatory drawings for Le Printemps, several are known: A pencil drawing heightened with chalk with a girl “turned, and seen almost in profile toward the left” with sheep in the left foreground, “one of which is suckling a lamb,” and the thatched roof of a cottage seen to the right, was listed in the sales catalogue for Very Valuable Modern and Ancient Paintings to be sold at the Plaza Hotel in New York on February 7, 1918, as no. 9, “A Shepherdess and Her Sheep: Spring Time.” This drawing was once in the collection of Samuel P. Avery, Jr., of New York.

[17] Cf. Shepherd, Sheep, and Lamb, reproduced in Hoeber (op.cit.); and a work by the same title sold at Christie’s in February 1988 (ex-Edward Laurence Doheny Collection, California). (This work is of the same dimensions as the Gallery 19c painting, and is also oil on canvas; see also Sale: Christie’s New York, October 12, 1993, lot 55). The motif of the nursing lamb reappears in numerous compositions as well.

[18] A small (16 x 11 ¾ in.) signed but undated version on panel, with only minor compositional differences, may be a study for this work. This painting, formerly in the collection of Isaac D. Fletcher, is described in some detail in a sales catalogue published by the American Art Association in 1918, making its similarities to the Gallery 19c version of Le Printemps clear: “The shepherdess, a young woman of rotund features and pensive expression, stands close in the foreground on the left, with her back to the spectator and face profil perdu against a gray and blue sky. A black kerchief confines her golden-brown hair, and she wears a gray cape with a brown hood, a skirt of crushed-strawberry hue and an apron of rich emerald-green – almost of malachite quality. Before her, at the right, is a gracefully straggling young tree in blossom, on whose root her staff or shepherd’s crook rests, and in front of and about the tree are two sheep and two lambs. One of the lambs, its soft fleece mellowed by a burst of sunlight, is suckling in the shelter of a gray, bleating ewe. In the distance are the thatched roofs of farm buildings,” (Illustrated Catalogue of Very Valuable Oil Paintings [New York: American Art Association, 1918], lot 25 [as Sheep and Shepherdess]). According to the annotations, this work sold to the dealer Knoedler for $2000.

A much later painting on a canvas of the same dimensions as the present work, dated 1881 and sold at Christie’s in May 1990 (lot 287, as Jeune Bergère Gardant ses Moutons), is in fact a collaborative effort between Jacque and the French landscape painter Louis Rémy Matifas (1847-1896); indeed, several contemporaries observed that Jacque’s late works were not entirely by his own hand (see (“My Note Book” by Montague Marks, The Art Amateur: A Monthly Journal Devoted to Art in the Household 32.3 [February 1895], p. 76).

[19] According to the accompanying descriptive catalogue, the sale of Zygomalas’s works in Paris at the Galerie Georges Petit on June 8, 1903 included a larger (“2 m. 15 x 1 m. 53”) replica of the present painting. A large work of similar dimensions was also listed (as Springtime) in the Illustrated Catalogue of Highly Important Collection of Master Works by Distinguished Painters . . . , sold at Chickering Hall on April 13 and 14, 1899 (no. 80) with the following note: “This most important example of the famous French sheep painter demonstrates again the artist’s profound knowledge of animals and his familiarity with their anatomy and construction.” Previously in the collection of E. M. Harris, the painting sold for $2000 to Jules Oehme of New York, an avid collector of Barbizon art and a dealer representing Boussod-Valadon & Co. The purchase was mentioned in the New York Times on April 14, 1899, with the price being described as a “low figure.” Zygomalas’s name is also mentioned in the Goupil stock books as the previous owner of what may be the present work (see Goupil stock book 14, op. cit.).

Like Zygomalas, Charles A. Gould may also have owned more than one version of Le Printemps – the smaller Met version and the Gallery 19c painting (see again Goupil stock book 14, op. cit.).

[20] Manuel Guiraldes (1857-1941) was but one of many notable Argentinian collectors who sought to add works by Jacque to his family collection. As a consequence of such individual and national interest, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires has several paintings by Jacque in its collection. For more on Buenos Aires’ role as an art center between 1880 and 1910, see María Isabel Baldasarre, “Buenos Aires: An Art Metropolis in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16.1 (Spring 2017), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring17/baldasarre-on-buenos-aires-an-art-metropolis-in-the-late-nineteenth-century.

Jacque was also a favorite among American collectors: Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) and Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919) were just two prominent collectors in the United States to own sheep paintings by the artist. (Frick is listed in the Knoedler stock books as purchasing a painting titled Le Printemps by Jacque in August 1895 [Knoedler stock book 4, stock no. 7864, p. 202, row 4]; the composition of this painting, however, differs from that of the present work.)