77.5 by 135.9 cm.

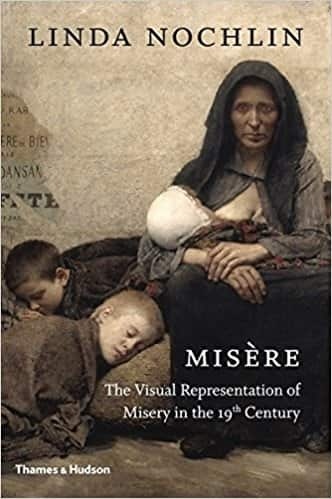

Sans Asile was Pelez's submission to the 1883 Salon, and also to the Exposition Universelle in 1889.

Provenance

Private collection, ArgentinaCatalogue note

Fernand Pelez was an Academically trained painter, who, like several other well-known artists of the period emerged from the workshop and tutelage of Alexandre Cabanel. Not surprisingly, his earliest works from the 1870s did not stray far from traditional Salon subjects, and in this he had some success. These early Salon entries were often sufficiently well regarded to be purchased by the French State. This would normally be considered a boon to the career of an artist and a source of encouragement along the well-established Academic path. But this was not to be the path he took.

Pelez apparently experienced a radical shift in artistic sensibility around this time which would be expressed by his choice of subjects for submission to the Salons of the 1880’s and for the rest of his career. His would turn his well-honed academic skills to the depiction of figures and scenes of the desperate and unfortunate of Belle Époque Paris – the homeless, child beggars, old men standing in bread lines, washerwomen and circus performers. The social implications of these iconoclastic and masterfully executed works had the effect one would expect at the time: critics often protested and official patronage dropped off.

Sans Asile was one of these pictures and his submission to the 1883 Salon, and also to the Exposition Universelle in 1889. More specifically, our painting is a previously unknown reduction of Sans Asile. It was not unusual for artists to make replicas of their paintings; this was a standard practice for many painters ranging from Bouguereau and Cabanel to Courbet.

There already existed an established tradition of depicting homeless or beggar families in art; artists such as Alexandre Antigna, William Bouguereau and Paul Delaroche had also painted the subject. Pelez, however, brings a new level of pathos to the interpretation, which previously had been more romanticized. Indeed, in Sans Asile we see a haggard and exhausted mother, aged beyond her years, nursing a baby, surrounded by her four older children. Their clothing and blankets are thread-bare, their few possessions forming a still-life on the right side of the composition. Mother and son stare out at the viewer. The mother’s expression is one of blank, weary resignation; the young boy’s eyes flash resentment and defiance. To help drive the point home, they are ironically placed against a backdrop of advertisements proclaiming a Grande Fête and dancing.

The scene in Sans Asile cannot help but bring to mind the Naturalist writings of Émile Zola, especially his novel l’Assommoir, a story of poverty and desperation set in the working class neighborhoods of Paris in the 1870s. Pelez paints what Zola writes about. In memorializing the tragic plight of the less fortunate; his subjects become more than art, they become a social commentary charged by a realism that is raw and uncensored. Following Pelez’s death, a full-page tribute was published in The New York Sun. His ability to champion the cause of the poor and downtrodden was not lost on the author, who wrote: "In calling him the painter of tramps, outcasts, the unfortunate, the world does not rightly christen him. He was a mystic, he bestowed on beggars the purest, finest pictorial execution that dreams can conceive. His brush has wiped tears of unjust sorrow from the face of the unhappy" (The New York Sun, 1914).

And as for his loss of official approval, it was only temporary. Today, Sans Asile is in the collection of the Petit Palais, having been part of a larger acquisition of Pelez’s paintings by the City of Paris in 1913 shortly after his death that same year. One can only guess what would have motivated such a purchase, given that the vagaries of fashion in art would seem not to have worked out in his favor. It may have been that, as art historian Robert Rosenblum put it in his comprehensive treatment of Pelez’s work: "…it also seems possible that, beneath his academic surfaces, Pelez was even for his time a singularly powerful and original artist and not one of type." (Robert Rosenblum, "Fernand Pelez, or The Other Side of the Post-Impressionist Coin," in The Ape of Nature, Studies in Honor of H.W. Janson, New York, 1981, p. 714).