Provenance

Gustave Courtois (1852-1923)

Private collection, thence by descent

Sale: Paris, Thierry de Maigret, 18 June 2009, lot 132 (as by Gustave Courtois)

Literature

Gabriel P. Weisberg, Against the Modern, Dagnan-Bouveret and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition, exh. cat., New York, Dahesh Museum of Art and Rutgers University Press, 2002, reproduced p. 112, fig. 120.

Catalogue note

French art at the end of the nineteenth century saw a resurgence in the depiction of sacred subjects. This was due in large part to the revitalization of the Catholic church, which dictated an ideology that was more relevant to modern culture. “Religious paintings seemed increasingly suggestive, abstract, and otherworldly as their creators were animated by a ‘new spirit,’ hoping to convert viewers on an intellectual and intuitive level…. They incorporated ‘modern symbolism’ to suggest the character of the period, and they personalized religious experience so that the viewers would become engrossed in the imagery.” (Gabriel P. Weisberg, Against the Modern: Dagnan-Bouveret and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition, New York, 2002, pp. 105-106). Artists such as Jean Béraud, Léon Lhermitte and James Tissot, whose The Life of Christ incorporated vivid realism with fantastic imagery in a series of 350 watercolors, turned their attention away from natural genre subjects and focused instead on scenes from the Life of Jesus Christ. Dagnan-Bouveret was at the forefront of this new spiritual movement in France.

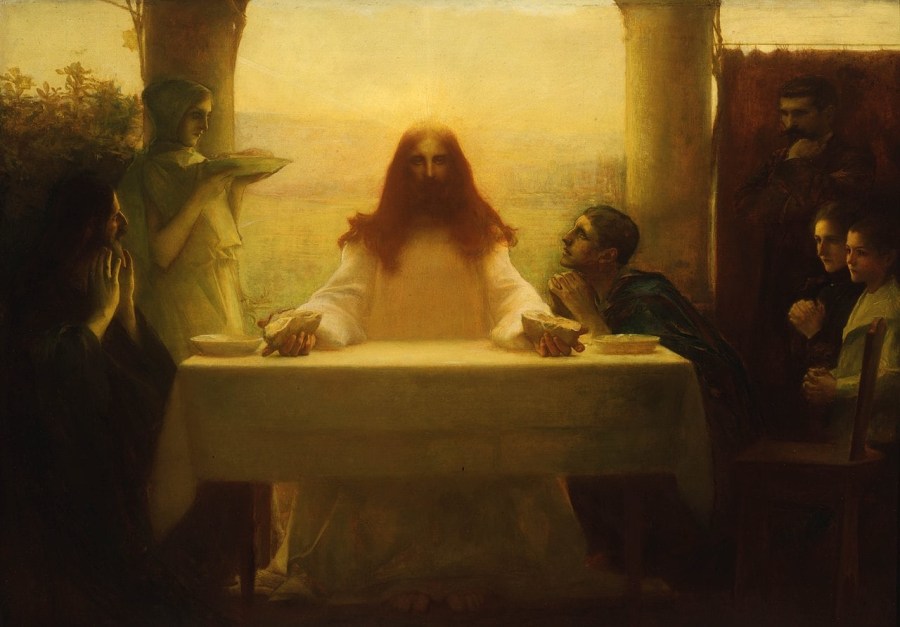

In 1887, Dagnan-Bouveret’s entry to the Paris Salon, The Pardon at Brittany (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) depicted a Breton religious custom showing a solemn procession of the faithful around a church. Penitents carry long tapers; some are barefoot displaying their contrition or kneel in prayer. How interesting to contemplate that in the next decade, Dagnan-Bouveret depicted what was at the core of the faith of these pious Breton pilgrims – their devotion to the Blessed Virgin and Her Son painted in a way “so that the viewers would become engrossed in the imagery.” (Ibid). Dagnan-Bouveret’s wife, Anne-Marie was a devout Catholic and her influence on the artist was transformative in the 1890s. “His Catholic faith and, in particular, the mystical presence of Christ and the Virgin seemed to bring him comfort, and this is reflected in his painting.” (Weisberg, p. 107). His most important sacred works from this period were The Madonna of the Trellis (1889, Private Collection), Christ at Gethsemane (ca. 1894, Location unknown), The Last Supper (1896, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (1896-1897, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh).

Our painting is a study for the donor figures on the right side of Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (fig.1). In the tradition of 15th century Netherlandish painting, where the donors are often included in the composition; Jan van Eyck’s The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin readily comes to mind, Dagnan-Bouveret has painted himself, his wife and son as witness to this moment in Saint Luke’s Gospel: “Now it came to pass, as He sat at the table with them, that He took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they knew Him; and He vanished from their sight.” (Luke 24: 30-31). The inclusion of the artist and his family in such a hallowed setting was a daring move by Dagnan-Bouveret, which both delighted and angered contemporary critics (see Weisberg, pp. 110-113). In addition to our oil painting, Dagnan-Bouveret made several preparatory drawings, and used photography to work out the individual poses in the final painting. Our study originally belonged to Gustave Courtois, Dagnan-Bouveret’s lifelong friend and fellow artist from their time together at the École des Beaux-Arts in the 1870s.

Dagnan-Bouveret exhibited Christ and His Disciples at Emmaus at the 1898 Paris Salon; it had already been purchased by Henry Clay Frick, where it joined other works by the artist in Frick’s Pittsburgh collection.