Provenance

Mario d’Atri, Paris, established around 1921

Gaetano Sperati, Milan

Private Collection, Milan

Private Collection, Italy, 1982

Thence by descent

Exhibited

Paris, Salon des artistes indépendants, 1910[1]Milan, Galleria d’Arte Sant’Ambrogio, La donna e i bimbi nell’arte del nostro Ottocento pittorico, 10 April – 4 May 1969, no. 50

[1] The pencil note on the stretcher indicates “salon des artistes indépendants, 1910” but the painting is not included in the exhibition catalogue

Literature

Mario Borgiotti, Incantesimi dell’Ottocento pittorico italiano, Milan, 1967

Enrico Piceni, Zandomeneghi, Milan, 1967, no. 310

Mario Borgiotti, Paul Nicholls, la donna e i bimbi nell’arte del nostro Ottocento pittorico, vol. III, Milan, 1969, no. 296

Enrico Piceni, Federico Zandomeneghi catalogo generale, Nuova edizione aggiornata e ampliata, Milan, 2006, no. 101, p. 219

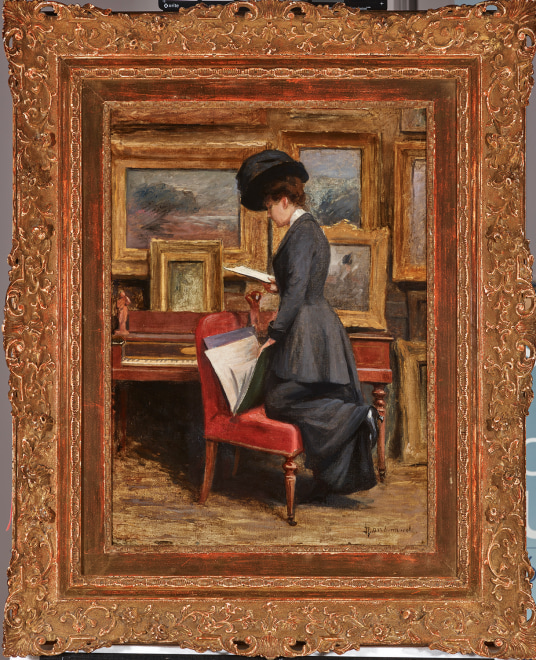

Catalogue note

When Venetian born, Federico Zandomeneghi arrived in Paris for the first time on June 2, 1874, he most likely did not know that he would soon play a part in the avant-garde art movement that would challenge the traditional and long-established trajectory of art history. The First Impressionist Exhibition, as it would eventually be called, had just closed its doors on May 15that 35 boulvevard des Capucines. “Zandò”, as he was nick-named by his French colleagues, would later join this modern movement in showing at subsequent shows in 1879, 1880, 1881 and 1886.

Upon arriving in Paris, Zandò was befriended and later mentored by Edgar Degas; the two artists had been introduced by a mutual friend, the Italian art critic and early supporter of Impressionism, Diego Martelli. Zandò also became a frequent presence at the Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes, where he mingled with Paris’s most famous avant-garde painters, writers, and musicians. However, it was the older Degas who exerted the greatest influence on Zandomeneghi. Like Degas, Zandò focused on showing women and girls involved in scenes of everyday life; this interest in realist subject matter also heralded an important feature in defining Impressionism in these nascent years of the movement. However, it is important to note that Zandomeneghi did indeed develop his own unique and recognizable painting style as he himself proclaimed, “as for my technique, a very vague term, the one I used was my own. I did not borrow from anyone.” (as quoted in Enrico Piceni, Zandomeneghi, n.p. 1991, p. 60).

The subject of our painting – that of a connoisseur or collector – was a subject often repeated by Degas; we think of his Collector of Prints from 1866 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) and The Amateurs, circa 1878 (Cleveland Museum of Art). However, the fact that our connoisseur is a woman is more reminiscent of Degas’s etching of Mary Cassatt at the Louvre, where the young American artist examines an Etruscan sarcophagus. Our model, with her knee casually resting on a red velvet chair as she peruses a portfolio of prints and drawings in an artist’s studio, like Mary Cassatt, is a symbol of the confident and independent woman making her presence felt in modern day Paris.